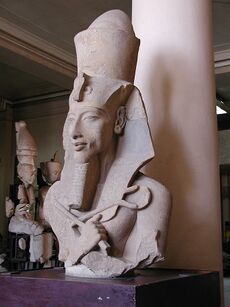

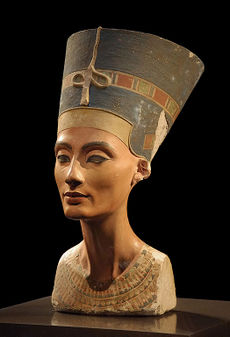

Ikhnaton and Nefertiti

The messengers Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet were embodied as Ikhnaton (Amenhotep IV) and Nefertiti, who ruled Egypt in the fourteenth century B.C. Pharaoh Ikhnaton (or Akhenaten, as the name is sometimes spelled) introduced a revolutionary religion into Egypt based on the worship of the one God, and he is remembered for having founded the first form of modern monotheism.

Early life

Ikhnaton lived during the New Kingdom period of the XVIIIth Dynasty in Egypt from approximately 1390 to 1360 B.C. He was the son of Amenhotep III, an incarnation of Serapis Bey. His great-great grandfather was Thutmose III, an incarnation of beloved Kuthumi, known as a mighty conqueror in battle.

Ikhnaton’s childhood is not spoken of. He did marry Nefertiti and they had six daughters. Soon after his marriage, he ascended to the throne of Egypt. He decided to break entirely with the old cults and make Aton the sole god.

There was such a corruption of the plurality of God that he went back to the original source to draw people’s attention away from the corrupt manifestations. We can see that Gautama Buddha had a similar purpose in his defining of the self. Sometimes it becomes necessary to remove all accoutrements of religious tradition when these become corrupted so that all can go back to the single source, the one God, the Father.

Ikhnaton’s monotheism

Ikhnaton recognized the one God in the spiritual Sun behind the physical sun, and he called this God “Aton.” Ikhnaton visualized the Infinite One, Aton, as a divine being “clearly distinguished from the physical sun” yet manifest in the sunlight. Ikhnaton gave reverence to the “heat which is in the Sun,” as he saw it to be the vital heat that accompanied all Life.[1]

Ikhnaton created a symbol that depicted Aton as a golden circular disk from which diverging beams radiated. He was careful to point out that the solar disk itself was not God but only a symbol of God. Each diverging beam, or ray, ended in a hand extending over every person as a blessing, and in some depictions the hand brought the ankh, the symbol of Life, directly to Ikhnaton and his Queen.

Ikhnaton also saw God as a personality whose “beams nourish every field” and “live and grow for thee.”[2] These beams are the very seeds of Light and sparks of Light that form our own threefold flame in the secret chamber of our heart. (Is this conception of the sun disc with its emanating rays not similar to the masters’ current instruction on the I AM Presence—the Sun of Righteousness—and the crystal cord through which the energies of the Sun descend to embodied man?)

Impatient with the practices of priests of Amon at Thebes, the king not only denounced their gods and ceremonies as a vulgar idolatry, but built a new capital for the kingdom, Akhetaten (known to archaeologists as Tel el Amarna), located nearly three hundred miles north of the ancient city of Thebes. Ikhnaton prohibited the worship of the old Nephilim gods, particularly Amon, the chief god, and ordered their names and images erased from the monuments. These were both embodied and disembodied fallen angels, to whom the black priests had erected their altars.

In his total loyalty to the one God of the Sun, Amenhotep IV changed his theophoric name to Ikhnaton, “He who is beneficial to Aton.” His passionate songs to Aton have been preserved as the fairest remnant of Egyptian literature.

- Thy dawning is beautiful in the horizon of the sky

- O Living Aton, Beginning of life.

- When thou risest in the eastern horizon,

- Thou fillest every land with thy beauty....

- How manifold are thy works!

- They are hidden from before us,

- O sole god, whose powers no other possesseth.

- Thou didst create the earth according to thy heart.[3]

Seven hundred years before Isaiah, Ikhnaton proclaimed the vitalistic conception of the Deity, found in the trees and flowers and all forms of Life—with the sun as the emblem of the ultimate power he now proclaims as the I AM Presence. Although the consciousness of the people was not ready for the one God in Ikhnaton’s day, the impact of monotheism is felt to the present day throughout the world’s great religions.

The end of their reign

Unfortunately, the reign of Ikhnaton and Nefertiti was but a tender interlude in Egypt’s era of power. An idealistic reformer, Ikhnaton was not wont to send Egyptians to war in defense of dependencies of Egypt that had been invaded. As a result, the Egyptian empire shrank, and the ruler found himself without funds or friends.

As Ikhnaton had no son, his oldest daughter was married to Smenkhkare, thereby making Smenkhkare the legitimate heir to the throne. Ikhnaton then associated Smenkhkare with him as co-regent.

In the seventeenth year of Ikhnaton’s reign and the third of the co-regency, he, his wife and the eldest daughter disappeared. Scholars have guessed that they were murdered. By whom and when and how is unknown. El Morya has shown us that it was the chief military leader, General Horemheb, who led a revolt against Ikhnaton and Nefertiti, and stabbed them to death.

The black priests reestablished the former gods and obliterated the name and image of Aton and Ikhnaton. Ikhnaton died at the age of thirty, having failed to accomplish his dreams, and his successor, Tutankhamen, reinstated the old gods and feast days and returned the capital to Thebes.

Influence on Judaism

Some have theorized that the monotheism of the Hebrews was founded upon the Egyptian pharaoh Ikhnaton’s worship of the one sun god. In about A.D. 80 the Jewish historian Josephus quoted Manetho, an Egyptian historian, as stating that Moses was a priest of the Egyptian city of Heliopolis who became the leader of a group of heretics (i.e., the Hebrews).

According to Hebrew tradition, Moses was raised in Egypt and is said to have been educated “in all the wisdom of the Egyptians”[4] at Heliopolis (the biblical city of On). Summarizing this theory, Robert Silverberg writes in his book Akhnaten: The Rebel Pharaoh:

Since Heliopolis was the center of the solar cult of Re, out of which Atenism developed, the wisdom Moses would have learned there could well have been the monotheistic solar worship that theologians of Heliopolis had pondered since the days of the Old Kingdom.[5]

Others argue that the dates of Moses and Ikhnaton are not at all certain and that the Exodus of the Hebrews may have occurred a century before Ikhnaton. In 1939 Sigmund Freud published Moses and Monotheism, in which he claimed that Moses was a native Egyptian and disciple of Ikhnaton who taught the religion of Aton to the Israelites.

Legacy

People who have commented on this life consider that Ikhnaton was poor in politics and diplomacy, that the revolution was so intense that it very soon destroyed him. But we understand that unless there be a cutting off by the ax at the root of error we cannot move on. We cannot allow the vines of Serpent to grow in our midst and expect that we are going to be able to prosper with the Tree of Life.

He understood the absolute, noncompromising attitude required with the fallen angels so much so that he reveals to us that we cannot afford to have sympathy with those who are the fallen angels and give them room and therefore allow their vibration to contaminate the Holy of Holies. This is the great message of Amarna—noncompromise. We do not compromise the living truth. And we do not give space to the false gods to appease their priests.

The devotion to Truth demonstrated by these rulers is typical of the qualities required for true messengers of God. Ikhnaton’s virtue was not in military victory or in political bargaining with the priests of Amon, but in his total lack of compromise with error.

His devotion to his queen was often publicly displayed and depicted in Egyptian art. The akashic records show that Ikhnaton had a great sense of mission to outpicture the principles of the Brotherhood, not only in his private life, but also in the laws of Egypt. The culture that the king and queen brought forth at Tel el Amarna in art, in poetry and in music was under the direction of the Brotherhood, inspired from Venus and the ancient lands of Mu and Atlantis when these civilizations were at their height.

James Breasted, the eminent Egyptologist, says of Ikhnaton:

There died with him such a spirit as the world had never seen before,—a brave soul, undauntedly facing the momentum of immemorial tradition, and thereby stepping out from the long line of conventional and colourless Pharaohs, that he might disseminate ideas far beyond and above the capacity of his age to understand. Among the Hebrews, seven or eight hundred years later, we look for such men; but the modern world has yet adequately to value or even acquaint itself with this man, who in an age so remote and under conditions so adverse, became the world’s first idealist and the world’s first individual ... the most remarkable of all the Pharaohs,... the first prophet of history.[6]

The bust of Nefertiti that can be seen today in a museum in Berlin is considered to be one of the masterpieces of the Amarna age. When one compares the portraits of Ikhnaton and Nefertiti with present-day photographs of the messengers, he will see how the characteristics of the soul are outpictured again and again in the physical form; indeed the physical form is the counterpart of the etheric. The resemblance may carry over for many embodiments until the traits change.

See also

For more information

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, Ikhnaton: Messenger of Aton (DVD).

Sources

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Path to Immortality.

Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 32, no. 65.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, June 21, 1981.

- ↑ James Henry Breasted, A History of Egypt: From the Earliest Times to the Persian Conquest (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912), pp. 360, 361.

- ↑ Cyril Aldred, Akhenaten: Pharaoh of Egypt (London: Thames and Hudson, Abacus, 1972), p. 133.

- ↑ Will Durant, The Story of Civilization (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1954) I:206, 208. Durant comments on this poem: “The obvious similarity of this hymn to Psalm CIV leaves little doubt of Egyptian influence upon the Hebrew poet” (p. 210).

- ↑ Acts 7:22.

- ↑ Robert Silverberg, Akhnaten: The Rebel Pharaoh (Philadelphia: Chilton Books, 1964 ), pp. 191–92.

- ↑ Breasted, A History of Egypt, pp. 393, 356, 377.