Bodhisattva/pl: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "W buddyjskiej szkole Mahajany, celem Ścieżki jest zostanie bodhisattwą. Ścieżka bodhisattwy jest ogólnie podzielona na dziesięć etapów, zwanych „bhumis”. Bodhisat...") |

PeterDuffy (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<languages/> | <languages/> | ||

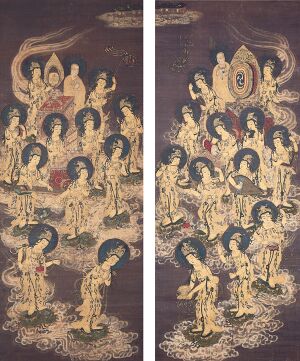

[[File:Twenty-Five Bodhisattvas Descending from Heaven, c. 1300.jpg|thumb|<span lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr">''Twenty-Five Bodhisattvas Descending from Heaven'', Japan, Kamakura period (c. 1300)</span>]] | |||

'''Bodhisattwa''' to termin sanskrycki oznaczający dosłownie istotę „bodhi” (lub oświecenia), istotę przeznaczoną do oświecenia lub taką, której energia i moc są skierowane ku oświeceniu. Bodhisattwa to ktoś, kto ma zostać [[Special:MyLanguage/Buddha|Buddą]], ale zrezygnował z błogości [[Special:MyLanguage/nirvana|nirwany]], ślubując zbawienie wszystkich dzieci Boga na ziemi. | |||

W buddyjskiej szkole Mahajany, celem Ścieżki jest zostanie bodhisattwą. Ścieżka bodhisattwy jest ogólnie podzielona na dziesięć etapów, zwanych „bhumis”. Bodhisattwa dąży do przechodzenia od jednego etapu do drugiego, aż osiągnie oświecenie. | W buddyjskiej szkole Mahajany, celem Ścieżki jest zostanie bodhisattwą. Ścieżka bodhisattwy jest ogólnie podzielona na dziesięć etapów, zwanych „bhumis”. Bodhisattwa dąży do przechodzenia od jednego etapu do drugiego, aż osiągnie oświecenie. | ||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

== The meaning of the word == | |||

</div> | |||

< | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | ||

Summarizing the bodhisattva ideal in Buddhism, Professors David Lopez and Steven Rockefeller write: | |||

</div> | |||

The Buddhist | <div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | ||

<blockquote> | |||

The Sanskrit term ''bodhisattva'' is composed of two words, ''bodhi'' and ''sattva''. ''Bodhi'' is derived from the verbal root ''budh'', meaning 'wake' so that ''bodhi'' is the state of being awake. | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

In the context of the Buddhist path, ''bodhi'' is the state of having awakened from the sleep of ignorance; it is enlightenment. | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

The second component of the term, sattva, can mean “sentient being,” in which case the compound ''bodhisattva'' would be read as “a being [seeking] enlightenment.”... | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

A second meaning of ''sattva'' is “mind” or “intention,” so that a Bodhisattva would be “one whose mind or intention is directed toward enlightenment.”... | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Bodhisattvas are unwilling to be satisfied merely by securing their own liberation and, deeply moved by the sight of the sufferings of other sentient beings, feel compassion for them and determine to become Buddhas so as to be able to provide the maximum benefit to others. | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

The Bodhisattva thus vows to become a Buddha in order to free all beings in the universe from suffering regardless of how many beings there are or how many aeons this might require.... | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Thus, the Bodhisattva is said to have two aims: the welfare of all sentient beings and the achievement of Buddhahood. | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

A Bodhisattva will be endowed with inconceivable wisdom, compassion and power and knowledge of limitless methods for freeing beings from suffering.<ref>''The Christ and The Bodhisattva'', Donald S. Lopez, Jr. and Steven C. Rockefeller, eds., (New York: State University of New York Press, 1987), pp. 24, 25.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

</div> | |||

Geshe Wangyal definiuje ''bodhisattwa'' jako | |||

<blockquote>„Potomstwo Zdobywcy”. Ten, który ślubował osiągnąć oświecenie dla dobra wszystkich żywych istot. Termin bodhisattwa odnosi się do tych na wielu poziomach: od tych, którzy po raz pierwszy zrodzili aspirację do oświecenia, aż po tych, którzy faktycznie wkroczyli na ścieżkę Bodhisattwy, która rozwija się przez dziesięć etapów i kończy się oświeceniem, osiągnięciem Stanu Buddy <ref>Geshe Wangyal, tłum., ''The Door of Liberation'' ''(Drzwi wyzwolenia)'' (Nowy Jork: Lotsawa, 1978), s. 208.</ref></blockquote> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

== The bodhisattva ideal == | |||

</div> | |||

Buddyjski filozof i mędrzec Nagardżuna w swojej książce napisanej około II wieku zdefiniował, czym jest bodhisattwa: | |||

<blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

Podstawową naturą wszystkich bodhisattwów jest wielkie kochające serce, a obiektem jego miłości są wszystkie czujące istoty. Dlatego wszyscy bodhisattwowie nie trzymają się błogiego smaku, który jest wytwarzany przez różne sposoby uspokojenia umysłu, nie pożądają owoców swoich chwalebnych czynów, które mogą zwiększyć ich własne szczęście... | |||

Z wielkim kochającym sercem patrzą na cierpienia wszystkich istot, które są różnorodnie torturowane w Piekle Avici w konsekwencji swoich grzechów – piekle, którego granice są nieskończone i gdzie możliwe jest nieskończone koło nieszczęścia z powodu wszelkiego rodzaju karmy [popełnione przez czujące stworzenia]. Bodhisattwowie przepełnieni litością i miłością pragną cierpieć dla dobra tych nieszczęsnych istot. | |||

Ale dobrze znają prawdę, że wszystkie te różnorodne cierpienia, powodujące różne stany nieszczęścia, są w pewnym sensie pozorne i nierzeczywiste, podczas gdy w innym sensie nie są takie .... | |||

Dlatego wszyscy bodhisattwowie, aby wyzwolić czujące istoty z nieszczęścia, natchnieni są wielką energią duchową i mieszają się w brudzie narodzin i śmierci. Chociaż w ten sposób poddają się prawom narodzin i śmierci, ich serca są wolne od grzechów i przywiązań. Są jak te niepokalane, nieskalane kwiaty lotosu, które wyrastają z błota, ale nie są nim zanieczyszczone. | |||

Ich wielkie współczujące serca, które stanowią esencję ich istnienia, nigdy nie pozostawiają cierpiących stworzeń za sobą [w ich podróży ku oświeceniu].<ref>Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, ''Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism'' (1907; przedruk, New York: Schocken Books, 1963),s. 292–94.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Scholar Har Dayal writes: | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

<blockquote> | |||

The ''bodhisattva'' ideal reminds us of the active altruism of the Franciscan friars in the thirteenth century <small>A</small>.<small>D</small>. as contrasted with the secluded and contemplative religious life of the Christian monks of that period. The monk prayed in solitude: the friar “went about doing good.”... | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Both the ''[[arhat]]'' [a Buddhist adept or saint] and the ''bodhisattva'' were unworldly idealists; but the ''arhat'' exhibited his idealism by devoting himself to meditation and self-culture, while the bodhisattva actively rendered service to other living beings.<ref>Har Dayal, ''The Bodhisattva Doctrine in Buddhist Sanskrit Literature'' (New York: Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1932), p. 29.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

== Bodhisattvas == | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

[[Maitreya]] | |||

</div> | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

[[Kuan Yin]] | |||

</div> | |||

<span id="For_more_information"></span> | |||

==Więcej informacji== | |||

{{MOI-pl}} | |||

== | <span id="Sources"></span> | ||

== Materiały źródłowe == | |||

{{ | {{SGA-pl}} | ||

{{MOI-pl}}. | |||

<div lang="en" dir="ltr" class="mw-content-ltr"> | |||

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, “The Age of Maitreya,” October 28, 1990. | |||

</div> | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 05:26, 7 July 2024

Bodhisattwa to termin sanskrycki oznaczający dosłownie istotę „bodhi” (lub oświecenia), istotę przeznaczoną do oświecenia lub taką, której energia i moc są skierowane ku oświeceniu. Bodhisattwa to ktoś, kto ma zostać Buddą, ale zrezygnował z błogości nirwany, ślubując zbawienie wszystkich dzieci Boga na ziemi.

W buddyjskiej szkole Mahajany, celem Ścieżki jest zostanie bodhisattwą. Ścieżka bodhisattwy jest ogólnie podzielona na dziesięć etapów, zwanych „bhumis”. Bodhisattwa dąży do przechodzenia od jednego etapu do drugiego, aż osiągnie oświecenie.

The meaning of the word

Summarizing the bodhisattva ideal in Buddhism, Professors David Lopez and Steven Rockefeller write:

The Sanskrit term bodhisattva is composed of two words, bodhi and sattva. Bodhi is derived from the verbal root budh, meaning 'wake' so that bodhi is the state of being awake.

In the context of the Buddhist path, bodhi is the state of having awakened from the sleep of ignorance; it is enlightenment.

The second component of the term, sattva, can mean “sentient being,” in which case the compound bodhisattva would be read as “a being [seeking] enlightenment.”...

A second meaning of sattva is “mind” or “intention,” so that a Bodhisattva would be “one whose mind or intention is directed toward enlightenment.”...

Bodhisattvas are unwilling to be satisfied merely by securing their own liberation and, deeply moved by the sight of the sufferings of other sentient beings, feel compassion for them and determine to become Buddhas so as to be able to provide the maximum benefit to others.

The Bodhisattva thus vows to become a Buddha in order to free all beings in the universe from suffering regardless of how many beings there are or how many aeons this might require....

Thus, the Bodhisattva is said to have two aims: the welfare of all sentient beings and the achievement of Buddhahood.

A Bodhisattva will be endowed with inconceivable wisdom, compassion and power and knowledge of limitless methods for freeing beings from suffering.[1]

Geshe Wangyal definiuje bodhisattwa jako

„Potomstwo Zdobywcy”. Ten, który ślubował osiągnąć oświecenie dla dobra wszystkich żywych istot. Termin bodhisattwa odnosi się do tych na wielu poziomach: od tych, którzy po raz pierwszy zrodzili aspirację do oświecenia, aż po tych, którzy faktycznie wkroczyli na ścieżkę Bodhisattwy, która rozwija się przez dziesięć etapów i kończy się oświeceniem, osiągnięciem Stanu Buddy [2]

The bodhisattva ideal

Buddyjski filozof i mędrzec Nagardżuna w swojej książce napisanej około II wieku zdefiniował, czym jest bodhisattwa:

Podstawową naturą wszystkich bodhisattwów jest wielkie kochające serce, a obiektem jego miłości są wszystkie czujące istoty. Dlatego wszyscy bodhisattwowie nie trzymają się błogiego smaku, który jest wytwarzany przez różne sposoby uspokojenia umysłu, nie pożądają owoców swoich chwalebnych czynów, które mogą zwiększyć ich własne szczęście...

Z wielkim kochającym sercem patrzą na cierpienia wszystkich istot, które są różnorodnie torturowane w Piekle Avici w konsekwencji swoich grzechów – piekle, którego granice są nieskończone i gdzie możliwe jest nieskończone koło nieszczęścia z powodu wszelkiego rodzaju karmy [popełnione przez czujące stworzenia]. Bodhisattwowie przepełnieni litością i miłością pragną cierpieć dla dobra tych nieszczęsnych istot.

Ale dobrze znają prawdę, że wszystkie te różnorodne cierpienia, powodujące różne stany nieszczęścia, są w pewnym sensie pozorne i nierzeczywiste, podczas gdy w innym sensie nie są takie ....

Dlatego wszyscy bodhisattwowie, aby wyzwolić czujące istoty z nieszczęścia, natchnieni są wielką energią duchową i mieszają się w brudzie narodzin i śmierci. Chociaż w ten sposób poddają się prawom narodzin i śmierci, ich serca są wolne od grzechów i przywiązań. Są jak te niepokalane, nieskalane kwiaty lotosu, które wyrastają z błota, ale nie są nim zanieczyszczone.

Ich wielkie współczujące serca, które stanowią esencję ich istnienia, nigdy nie pozostawiają cierpiących stworzeń za sobą [w ich podróży ku oświeceniu].[3]

Scholar Har Dayal writes:

The bodhisattva ideal reminds us of the active altruism of the Franciscan friars in the thirteenth century A.D. as contrasted with the secluded and contemplative religious life of the Christian monks of that period. The monk prayed in solitude: the friar “went about doing good.”...

Both the arhat [a Buddhist adept or saint] and the bodhisattva were unworldly idealists; but the arhat exhibited his idealism by devoting himself to meditation and self-culture, while the bodhisattva actively rendered service to other living beings.[4]

Bodhisattvas

Więcej informacji

Materiały źródłowe

Mark L. Prophet i Elizabeth Clare Prophet: „Saint Germain: o alchemii. Formuły przemiany samego siebie”

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, “The Age of Maitreya,” October 28, 1990.

- ↑ The Christ and The Bodhisattva, Donald S. Lopez, Jr. and Steven C. Rockefeller, eds., (New York: State University of New York Press, 1987), pp. 24, 25.

- ↑ Geshe Wangyal, tłum., The Door of Liberation (Drzwi wyzwolenia) (Nowy Jork: Lotsawa, 1978), s. 208.

- ↑ Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism (1907; przedruk, New York: Schocken Books, 1963),s. 292–94.

- ↑ Har Dayal, The Bodhisattva Doctrine in Buddhist Sanskrit Literature (New York: Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1932), p. 29.