Padre Pio: Difference between revisions

(translate tags) |

PeterDuffy (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<languages /> | <languages /> | ||

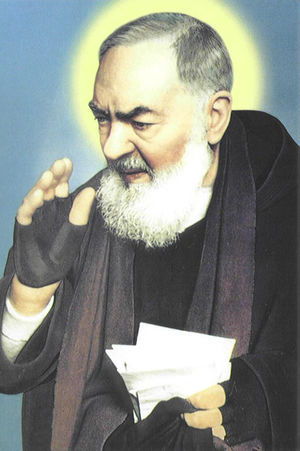

[[File:PadrePio.jpg|thumb|<translate>Padre Pio</translate>]] | [[File:PadrePio.jpg|thumb|<translate><!--T:1--> Padre Pio</translate>]] | ||

<translate> | <translate> | ||

<!--T:2--> | |||

'''Padre Pio''' was the famous twentieth-century Italian monk who for fifty years bore on his hands, feet and side the wounds of the crucified Christ, called the [[stigmata]]. | '''Padre Pio''' was the famous twentieth-century Italian monk who for fifty years bore on his hands, feet and side the wounds of the crucified Christ, called the [[stigmata]]. | ||

== His life == | == His life == <!--T:3--> | ||

<!--T:4--> | |||

This gentle, humble priest was born Francesco Forgione on May 25, 1887, in one of the poorest and most backward areas of southern Italy. At the age of fifteen, he entered a Franciscan Capuchin monastery, and he was ordained into the priesthood in 1910. | This gentle, humble priest was born Francesco Forgione on May 25, 1887, in one of the poorest and most backward areas of southern Italy. At the age of fifteen, he entered a Franciscan Capuchin monastery, and he was ordained into the priesthood in 1910. | ||

<!--T:5--> | |||

He served in World War I in the medical corps, but was too sickly to continue. In 1918 he was transferred to the small sixteenth-century friary of Our Lady of Grace, about two hundred miles east of Rome. From then on, he never left this isolated mountain area. Yet, by the time of his death in 1968, he was receiving five thousand letters a month and thousands of visitors. He had become renowned for his piety and his miracles. | He served in World War I in the medical corps, but was too sickly to continue. In 1918 he was transferred to the small sixteenth-century friary of Our Lady of Grace, about two hundred miles east of Rome. From then on, he never left this isolated mountain area. Yet, by the time of his death in 1968, he was receiving five thousand letters a month and thousands of visitors. He had become renowned for his piety and his miracles. | ||

<!--T:6--> | |||

Padre Pio is thought to be the first Catholic priest to bear the wounds of Christ. ([[Saint Francis]] was the first person known to have received the stigmata.) He also had the gifts of spiritual clairvoyance, conversion, discernment of spirits, visions, bilocation, healing and prophecy. It is said that once when a newly ordained Polish priest came to see him, Padre Pio remarked: “Someday you will be pope.” As prophesied, that priest became Pope John Paul II. | Padre Pio is thought to be the first Catholic priest to bear the wounds of Christ. ([[Saint Francis]] was the first person known to have received the stigmata.) He also had the gifts of spiritual clairvoyance, conversion, discernment of spirits, visions, bilocation, healing and prophecy. It is said that once when a newly ordained Polish priest came to see him, Padre Pio remarked: “Someday you will be pope.” As prophesied, that priest became Pope John Paul II. | ||

<!--T:7--> | |||

Padre Pio spoke frequently in visions with [[Jesus]], [[Mother Mary|Mary]] and his own [[guardian angel]]. On other occasions he spent the night in intense struggles with the Devil. The Padre would be found in the morning with blood and bruises and other physical signs of the struggle. He was often exhausted, sometimes unconscious, and on one occasion suffered from broken bones in his body. On one occasion the iron bars of the window were twisted. Other monks often heard the noise of these encounters, although only Padre Pio saw the demons. | Padre Pio spoke frequently in visions with [[Jesus]], [[Mother Mary|Mary]] and his own [[guardian angel]]. On other occasions he spent the night in intense struggles with the Devil. The Padre would be found in the morning with blood and bruises and other physical signs of the struggle. He was often exhausted, sometimes unconscious, and on one occasion suffered from broken bones in his body. On one occasion the iron bars of the window were twisted. Other monks often heard the noise of these encounters, although only Padre Pio saw the demons. | ||

<!--T:8--> | |||

As well as these invisible assaults, Padre Pio also suffered the persecution of people within the hierarchy of his beloved Church. For ten years he was not permitted to serve Mass publicly or hear confessions. | As well as these invisible assaults, Padre Pio also suffered the persecution of people within the hierarchy of his beloved Church. For ten years he was not permitted to serve Mass publicly or hear confessions. | ||

== His service as a confessor == | == His service as a confessor == <!--T:9--> | ||

<!--T:10--> | |||

One of the things Padre Pio was most famous for was his ability as a confessor. Kenneth Woodward writes: “Most of Padre Pio’s energies were devoted to intense prayer, celebrating Mass and, above all, hearing confessions.” People from around the world flocked to his doorstep to have him hear their confessions. Woodward says: | One of the things Padre Pio was most famous for was his ability as a confessor. Kenneth Woodward writes: “Most of Padre Pio’s energies were devoted to intense prayer, celebrating Mass and, above all, hearing confessions.” People from around the world flocked to his doorstep to have him hear their confessions. Woodward says: | ||

<blockquote>Padre Pio is credited with the gift of “reading hearts”—that is, the ability to see into the souls of others and know their sins without hearing a word from the penitent. As his reputation grew, so did the lines outside his confessional—to the point that for a time his fellow Capuchins issued tickets for the privilege of confessing to Padre Pio. Sometimes, when a sinner could not come to him, Padre Pio went to the sinner, it is said, though not in the usual manner. | <!--T:11--> | ||

<blockquote> | |||

Padre Pio is credited with the gift of “reading hearts”—that is, the ability to see into the souls of others and know their sins without hearing a word from the penitent. As his reputation grew, so did the lines outside his confessional—to the point that for a time his fellow Capuchins issued tickets for the privilege of confessing to Padre Pio. Sometimes, when a sinner could not come to him, Padre Pio went to the sinner, it is said, though not in the usual manner. | |||

< | <!--T:12--> | ||

Without leaving his room, the friar would appear as far away as Rome to hear a confession or comfort the sick. He was endowed, in other words, with the power of “bilocation,” or the ability to be present in two places at once.<ref>Kenneth L. Woodward, ''Making Saints: How the Catholic Church Determines Who Becomes a Saint, Who Doesn’t, and Why'' (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), p. 156–57.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

<!--T:13--> | |||

Sometimes Padre Pio treated those who came to him for confession sternly. One of his devotees wrote: | Sometimes Padre Pio treated those who came to him for confession sternly. One of his devotees wrote: | ||

<!--T:14--> | |||

<blockquote>If he is sometimes severe, it is because many people approach the confessional lightly, without giving the sacrament its true importance.<ref>Laura Chandler White, trans., ''Who is Padre Pio?'' (Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books, 1974), p. 41.</ref></blockquote> | <blockquote>If he is sometimes severe, it is because many people approach the confessional lightly, without giving the sacrament its true importance.<ref>Laura Chandler White, trans., ''Who is Padre Pio?'' (Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books, 1974), p. 41.</ref></blockquote> | ||

</translate> | </translate> | ||

[[File:Padre Pio during Mass.jpg|thumb|<translate>Padre Pio celebrating Mass</translate>]] | [[File:Padre Pio during Mass.jpg|thumb|<translate><!--T:15--> Padre Pio celebrating Mass</translate>]] | ||

<translate> | <translate> | ||

<!--T:16--> | |||

Many people were transformed who came to hear Padre Pio celebrate the Mass. The same devotee writes: | Many people were transformed who came to hear Padre Pio celebrate the Mass. The same devotee writes: | ||

<blockquote>When the hour of Mass approaches, all faces are turned toward the sacristy from which the Padre will come, seeming to walk painfully on his pierced feet. We feel that grace itself is approaching us, forcing us to bend our knees. Padre Pio is not an ordinary priest, but a creature in pain who renews the Passion of Christ with the devotion and radiance of one who is inspired by God. | <!--T:17--> | ||

<blockquote> | |||

When the hour of Mass approaches, all faces are turned toward the sacristy from which the Padre will come, seeming to walk painfully on his pierced feet. We feel that grace itself is approaching us, forcing us to bend our knees. Padre Pio is not an ordinary priest, but a creature in pain who renews the Passion of Christ with the devotion and radiance of one who is inspired by God. | |||

< | <!--T:18--> | ||

After he steps to the altar and makes the Sign of the Cross, the Padre’s face is transfigured, and he seems like a creature who becomes one with his Creator. Tears roll down his cheeks, and from his mouth come words of prayer, of supplication for pardon, of love for his Lord of whom he seems to become a perfect replica. None of those present notice the passage of time. It takes him about one hour and a half to say his mass, but the attention of all is riveted on every gesture, movement and expression of the celebrant. | |||

< | <!--T:19--> | ||

At the sound of the word “Credo” pronounced with such tremendous conviction, there is a great wave of emotion through the throng. And the most recalcitrant of sinners is carried along as on a stream that is bringing him to the confessional and the renunciation of his old way of life.<ref>Ibid., pp. 39–40.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

== Miracle-worker == | == Miracle-worker == <!--T:20--> | ||

<!--T:21--> | |||

Author Stuart Holroyd relates just a few of the many stories of Padre Pio’s miraculous intercession. He writes: | Author Stuart Holroyd relates just a few of the many stories of Padre Pio’s miraculous intercession. He writes: | ||

<blockquote>During World War I, an Italian general, after a series of defeats, was on the point of committing suicide when a monk entered his tent and said: “Such an action is foolish,” and promptly left. The general didn’t hear of the existence of Padre Pio until some time later, but when he visited the monastery, he identified him as the monk who had appeared at a crucial moment and saved his life. | <!--T:22--> | ||

<blockquote> | |||

During World War I, an Italian general, after a series of defeats, was on the point of committing suicide when a monk entered his tent and said: “Such an action is foolish,” and promptly left. The general didn’t hear of the existence of Padre Pio until some time later, but when he visited the monastery, he identified him as the monk who had appeared at a crucial moment and saved his life. | |||

< | <!--T:23--> | ||

During World War II an Italian pilot baled out of a blazing plane. His parachute failed to open but he miraculously fell to the ground without injury, and he returned to his base with a strange story to tell. When he had been falling to the ground, a friar had caught him in his arms and carried him gently down to earth. His Commanding Officer said he was obviously suffering from shock, and sent him home on leave. | |||

< | <!--T:24--> | ||

When he told his mother the tale of his escape, she said: “That was Padre Pio. I prayed to him so hard for you.” Then she showed him a picture of the Padre. “That is the man!” said the young pilot. | |||

< | <!--T:25--> | ||

He later went to thank the padre for his intervention. “That is not the only time I have saved you,” said Padre Pio. “At Monastir, when your plane was hit, I made it glide safely to earth.” The pilot was astounded because the event the Padre referred to had happened some time before, and there was no normal way he could have known about it.<ref>Stuard Holroyd, ''Psychic Voyages'' (London: Danbury Press, 1976), p. 44–45.</ref> | |||

</blockquote> | |||

== His service today == | == His service today == <!--T:26--> | ||

<!--T:27--> | |||

In 1975, some seven years after his death, the ascended lady master [[Clara Louise]] told us that Padre Pio is an ascended master. Padre Pio is instrumental in assisting the [[Church Universal and Triumphant|Church the masters have founded]] in the [[Aquarian age]]. He is also renowned for his ability to answer prayers for healing. Padre Pio was officially recognized as a saint of the Catholic Church on June 16, 2002. | In 1975, some seven years after his death, the ascended lady master [[Clara Louise]] told us that Padre Pio is an ascended master. Padre Pio is instrumental in assisting the [[Church Universal and Triumphant|Church the masters have founded]] in the [[Aquarian age]]. He is also renowned for his ability to answer prayers for healing. Padre Pio was officially recognized as a saint of the Catholic Church on June 16, 2002. | ||

== Sources == | == Sources == <!--T:28--> | ||

<!--T:29--> | |||

{{MTR}}, s.v. “Padre Pio.” | {{MTR}}, s.v. “Padre Pio.” | ||

<!--T:30--> | |||

[[Category:Heavenly beings]] | [[Category:Heavenly beings]] | ||

</translate> | </translate> | ||

[[Category:Christian saints{{#translation:}}]] | |||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 04:32, 9 July 2024

Padre Pio was the famous twentieth-century Italian monk who for fifty years bore on his hands, feet and side the wounds of the crucified Christ, called the stigmata.

His life

This gentle, humble priest was born Francesco Forgione on May 25, 1887, in one of the poorest and most backward areas of southern Italy. At the age of fifteen, he entered a Franciscan Capuchin monastery, and he was ordained into the priesthood in 1910.

He served in World War I in the medical corps, but was too sickly to continue. In 1918 he was transferred to the small sixteenth-century friary of Our Lady of Grace, about two hundred miles east of Rome. From then on, he never left this isolated mountain area. Yet, by the time of his death in 1968, he was receiving five thousand letters a month and thousands of visitors. He had become renowned for his piety and his miracles.

Padre Pio is thought to be the first Catholic priest to bear the wounds of Christ. (Saint Francis was the first person known to have received the stigmata.) He also had the gifts of spiritual clairvoyance, conversion, discernment of spirits, visions, bilocation, healing and prophecy. It is said that once when a newly ordained Polish priest came to see him, Padre Pio remarked: “Someday you will be pope.” As prophesied, that priest became Pope John Paul II.

Padre Pio spoke frequently in visions with Jesus, Mary and his own guardian angel. On other occasions he spent the night in intense struggles with the Devil. The Padre would be found in the morning with blood and bruises and other physical signs of the struggle. He was often exhausted, sometimes unconscious, and on one occasion suffered from broken bones in his body. On one occasion the iron bars of the window were twisted. Other monks often heard the noise of these encounters, although only Padre Pio saw the demons.

As well as these invisible assaults, Padre Pio also suffered the persecution of people within the hierarchy of his beloved Church. For ten years he was not permitted to serve Mass publicly or hear confessions.

His service as a confessor

One of the things Padre Pio was most famous for was his ability as a confessor. Kenneth Woodward writes: “Most of Padre Pio’s energies were devoted to intense prayer, celebrating Mass and, above all, hearing confessions.” People from around the world flocked to his doorstep to have him hear their confessions. Woodward says:

Padre Pio is credited with the gift of “reading hearts”—that is, the ability to see into the souls of others and know their sins without hearing a word from the penitent. As his reputation grew, so did the lines outside his confessional—to the point that for a time his fellow Capuchins issued tickets for the privilege of confessing to Padre Pio. Sometimes, when a sinner could not come to him, Padre Pio went to the sinner, it is said, though not in the usual manner.

Without leaving his room, the friar would appear as far away as Rome to hear a confession or comfort the sick. He was endowed, in other words, with the power of “bilocation,” or the ability to be present in two places at once.[1]

Sometimes Padre Pio treated those who came to him for confession sternly. One of his devotees wrote:

If he is sometimes severe, it is because many people approach the confessional lightly, without giving the sacrament its true importance.[2]

Many people were transformed who came to hear Padre Pio celebrate the Mass. The same devotee writes:

When the hour of Mass approaches, all faces are turned toward the sacristy from which the Padre will come, seeming to walk painfully on his pierced feet. We feel that grace itself is approaching us, forcing us to bend our knees. Padre Pio is not an ordinary priest, but a creature in pain who renews the Passion of Christ with the devotion and radiance of one who is inspired by God.

After he steps to the altar and makes the Sign of the Cross, the Padre’s face is transfigured, and he seems like a creature who becomes one with his Creator. Tears roll down his cheeks, and from his mouth come words of prayer, of supplication for pardon, of love for his Lord of whom he seems to become a perfect replica. None of those present notice the passage of time. It takes him about one hour and a half to say his mass, but the attention of all is riveted on every gesture, movement and expression of the celebrant.

At the sound of the word “Credo” pronounced with such tremendous conviction, there is a great wave of emotion through the throng. And the most recalcitrant of sinners is carried along as on a stream that is bringing him to the confessional and the renunciation of his old way of life.[3]

Miracle-worker

Author Stuart Holroyd relates just a few of the many stories of Padre Pio’s miraculous intercession. He writes:

During World War I, an Italian general, after a series of defeats, was on the point of committing suicide when a monk entered his tent and said: “Such an action is foolish,” and promptly left. The general didn’t hear of the existence of Padre Pio until some time later, but when he visited the monastery, he identified him as the monk who had appeared at a crucial moment and saved his life.

During World War II an Italian pilot baled out of a blazing plane. His parachute failed to open but he miraculously fell to the ground without injury, and he returned to his base with a strange story to tell. When he had been falling to the ground, a friar had caught him in his arms and carried him gently down to earth. His Commanding Officer said he was obviously suffering from shock, and sent him home on leave.

When he told his mother the tale of his escape, she said: “That was Padre Pio. I prayed to him so hard for you.” Then she showed him a picture of the Padre. “That is the man!” said the young pilot.

He later went to thank the padre for his intervention. “That is not the only time I have saved you,” said Padre Pio. “At Monastir, when your plane was hit, I made it glide safely to earth.” The pilot was astounded because the event the Padre referred to had happened some time before, and there was no normal way he could have known about it.[4]

His service today

In 1975, some seven years after his death, the ascended lady master Clara Louise told us that Padre Pio is an ascended master. Padre Pio is instrumental in assisting the Church the masters have founded in the Aquarian age. He is also renowned for his ability to answer prayers for healing. Padre Pio was officially recognized as a saint of the Catholic Church on June 16, 2002.

Sources

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Masters and Their Retreats, s.v. “Padre Pio.”

- ↑ Kenneth L. Woodward, Making Saints: How the Catholic Church Determines Who Becomes a Saint, Who Doesn’t, and Why (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), p. 156–57.

- ↑ Laura Chandler White, trans., Who is Padre Pio? (Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books, 1974), p. 41.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Stuard Holroyd, Psychic Voyages (London: Danbury Press, 1976), p. 44–45.