Confucius/ru: Difference between revisions

PeterDuffy (talk | contribs) (Created page with "Конфуций") |

PeterDuffy (talk | contribs) (Created page with "Конфуций") |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<languages /> | <languages /> | ||

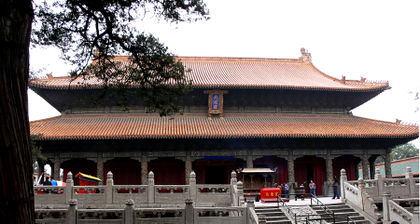

[[File:Confucio (Master Kong Qiu).jpg|thumb| | [[File:Confucio (Master Kong Qiu).jpg|thumb|Конфуций]] | ||

'''Confucius''' is hierarch of the [[Royal Teton Retreat]], and he serves on the second ray of divine wisdom. He succeeded [[Lord Lanto]] as hierarch of the Retreat on July 3, 1958. | '''Confucius''' is hierarch of the [[Royal Teton Retreat]], and he serves on the second ray of divine wisdom. He succeeded [[Lord Lanto]] as hierarch of the Retreat on July 3, 1958. | ||

Revision as of 14:04, 27 March 2022

Confucius is hierarch of the Royal Teton Retreat, and he serves on the second ray of divine wisdom. He succeeded Lord Lanto as hierarch of the Retreat on July 3, 1958.

Confucius’ legacy

Although he has had many embodiments of service to the light, Confucius is best remembered for his contributions to the Chinese way of life. Known as K’ung Fu-tze (“Philosopher K’ung” or “Master K’ung”) to his contemporaries in the 5th century B.C., he set the stage for the eventual unification and administration of the Chinese empire. A brilliant social, economic, political and moral philosopher, Confucius laid the theoretical foundations that enabled China to become one of the greatest civilizations of all time. Despite the rise and fall of dynasties, the Confucian state prevailed; and eventually, through the spread of Chinese culture, his ideas were accepted throughout Eastern Asia. Seldom has one man influenced more people over a greater period of time.

Confucius is honored as China’s greatest teacher and has been worshiped as a great bodhisattva, or future Buddha. He believed that heaven could be created on earth through ritual and music. His followers became known as Knights of the Arts because they mastered archery, poetry, mathematics, history, dance, religious rituals and etiquette.

While later generations misinterpreted Confucius and thought him to be a stuffy bureaucrat, Confucius had a profound spirituality and vision. That is why he was so practical. Confucius taught: “The Path may not be left for an instant. If it could be left, it would not be the Path.”[1] Despite the effort to purge his teachings, sayings of Confucius such as “The demands that a gentleman makes are upon himself; those that a small man makes are upon others”[2] and “The cautious seldom err”[3] remain an integral part of the thinking of the Chinese people.

Confucius’ life

Confucius was born in 551 B.C., a time of great turmoil and chaos. His father, an elderly soldier, died when he was three. Although his family was poor, he managed to educate himself. When he was fifteen, he knew he wanted to be a scholar. He worked as a clerk at the memorial temple of the Duke of Chou, one of the greatest statesmen in Chinese history.

Five hundred years earlier, the Duke of Chou, his father, King Wen, and his brother had overthrown the corrupt Shang dynasty and established the Chou dynasty. He brought a new understanding of God and divine government to the Chinese people. “I am only concerned with Heaven and the people,”[4] he had said.

Confucius believed that the Duke of Chou was teaching him in his dreams at night. In fact, Confucius claimed that he himself was not an innovator—he was only bringing back the standard and the principles of the Duke of Chou. (The Duke of Chou was an embodiment of Lord Lanto, and it is believed that Confucius was embodied at the time of the Duke of Chou and helped him implement his ideals.)

Inspired by the Duke of Chou, Confucius edited the six Chinese classics, which had been written by King Wen. These were the Book of Poetry, the Book of Rites, the Book of History, the Book of Change (I Ching), the Book of Documents and the Book of Music. The Book of Music, unfortunately, has been completely lost.

Today Confucius has a reputation for being stiff and reserved. But he was not without sensitivity. The story is told that he was once so moved by a performance of ancient music that he remained in a stupor for three months. When he finally came out of the trance, he said, “I never imagined that music could be so sublime.”[5]

We do not know much about Confucius’ life. He was married when he was nineteen and had a son and a daughter. He studied under various teachers and eventually gathered a group of students around him. For a time, he held a job as justice minister but was forced to abandon it and go into exile. Although Confucius had seventy-two disciples and more than three thousand students, he never realized his dream of becoming a prominent ruler in China.

During this time, the Chou dynasty was on the verge of collapse. The Chou government had degenerated into chaos, and brutal warlords continually fought with each other. “Confucius was the first to formulate a systematic response to this crisis in values,” writes Robert Eno, scholar of Chinese thought. “And the depth of his achievement is reflected by the fact that China’s first philosopher remained throughout its history its leading philosopher.”[6]

Confucius believed that ritual, or li, could transform one’s identity, one’s mind, one’s very being. “The program of study begins with the chanting of texts and ends with the study of ritual li,” Confucius explained. “Its significance is that one begins by becoming a gentleman and ends by becoming a Sage.”[7] Through disciplined cultivation of li, one attained jen, which Eno describes as “the selfless ethical responsiveness to others.”[8]

Although Confucius traveled throughout China, he never found a suitable job in the government. He felt like a failure and started to lament: “Extreme indeed is my decline. It’s been a long time since I dreamt about the Duke of Chou.”[9]

Confucius did not realize it at the time, but his spirituality was far more powerful than his resumé. He wandered about looking for work, but what he was really doing was anchoring his spiritual flame of wisdom in every corner of China. That flame inspired and sustained Chinese culture for many centuries.

His service today

As an ascended master, Confucius still dreams of making a heaven on earth through divine government. While he has not been able to work this dream in China, he sees himself as the grandfather of America. With practical wisdom and deep love, he inspires and guides his disciples who have embodied in the United States. Lanto explains that the practical side of the culture of America comes from the causal body of Confucius.

The ascended master Confucius has a profound understanding of family as the vital unit for building community and a new society in the Aquarian age. He shows us how to take etheric patterns and use them in tangible ways to improve our everyday lives—patterns of self-reliance in God, of the sacred family and of God-government. We tie into the etheric patterns and precipitate the etheric ideals through beauty, harmony and order in the physical octave. This is why the flame of precipitation is the main focus of Confucius’ Royal Teton Retreat. This flame is Chinese green in color, tinged with gold, and it burns on the main altar of the Retreat.

Confucius wants us to regard him as our loving and supportive grandfather. And like a grandfather, he also desires to pass on his dreams to us that we might fulfill them in his name. He longs to build a society on the foundation of love, wisdom and the will of God in the individual and in the family.

In 1976, Confucius said that many souls from ancient China have reembodied in America. He called them “the quiet Buddhic souls, the diligent ones,” the ones who have a spiritual mission to lay the foundation of the family in America. He points out that they understand the “basic loyalty of the family, the code of ethics, the gentleness, the sweetness and the desire for learning as the means to God-awareness.”

Furthermore, Confucius said, “They have come for an embodiment that their wisdom might be fired with freedom, that they might assist America” as she enters the twenty-first century. Their aim is to turn around a “false materialism” and to manifest instead “an etherealization, a spirituality, a conquering of self, of society and of the energies of time and space.”

Confucius is very much concerned with the affairs of civilization and with the destiny of America:

I am concerned on the one hand with the activities of the masculine ray as that ray has been perverted in China today and as its perversion has also led to the perversion of the feminine ray and the manifestation of the family.

I have seen the corruption in government. It is the same corruption that I witnessed twenty-five hundred years ago—the same corruption, mind you, the same corruptible ones. For the lifestreams who are focusing the energies for the disintegration of the light and of the golden age of China today are the lifestreams who thwarted the cosmic purpose of the Virgin thousands of years ago when my feet touched the earth and the streams of that beloved land of Chin.

I have noticed also that those who are the corruptible ones who have corrupted Saint Germain’s promise for America have come again and again. It is they who were the rats in the granary of Rome and Greece, India, the Middle East. There are always the betrayers.[10]

Confucius has said:

It is only cosmic justice that a balance should be made for the expenditure of every ounce of energy. Through the aeons and aeons of creation, this great law has never been violated with impunity. And those who think they can violate divine statutes have quickly found out upon the cosmic screen of life that the scales of divine justice do act, and that they act wisely and well.[11]

Sources

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Masters and Their Retreats, s.v. “Confucius.”

- ↑ Confucius, The Doctrine of the Mean, trans. James Legge.

- ↑ Confucius, Analects, 15:20, trans. Arthur Waley.

- ↑ Confucius, Analects, 4:23.

- ↑ The Duke of Chou, quoted in Herrlee G. Greel, The Origins of Statecraft in China (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970), 1:98.

- ↑ Confucius, Analects, 7:13, trans. James Legge.

- ↑ Robert Eno, The Confucian Creation of Heaven: Philosophy and the Defense of Ritual Mastery (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1990), p. 2.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 3.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 5.

- ↑ Confucius, Analects, 7:5.

- ↑ Confucius, “The Golden Light of the Golden Age of China,” June 13, 1976.

- ↑ Confucius, July 3, 1962.