Catherine of Siena: Difference between revisions

(new material) |

(added images) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

For the next three years Catherine remained cloistered in a small room in her father’s house, living a life of austerity, solitude and silence, withdrawing into the “inner cell” of the knowledge of God and self, as she described her communion with the Lord. She had many visions and conversations with [[Jesus]], culminating in the spiritual marriage with Christ. During that time Catherine received Jesus’ teaching “I, nothing; God, All. I, nonbeing; God, Being.” This fundamental truth inspired in her the humility and the conviction that enabled her to confront the forces threatening the Church and society in the turbulent fourteenth century. | For the next three years Catherine remained cloistered in a small room in her father’s house, living a life of austerity, solitude and silence, withdrawing into the “inner cell” of the knowledge of God and self, as she described her communion with the Lord. She had many visions and conversations with [[Jesus]], culminating in the spiritual marriage with Christ. During that time Catherine received Jesus’ teaching “I, nothing; God, All. I, nonbeing; God, Being.” This fundamental truth inspired in her the humility and the conviction that enabled her to confront the forces threatening the Church and society in the turbulent fourteenth century. | ||

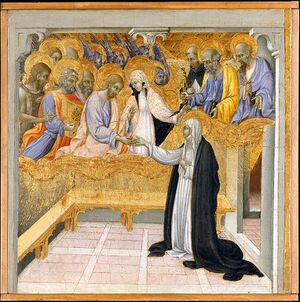

[[File:1018px-Giovanni di Paolo The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena.jpg|thumb|The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine of Siena, Giovanni di Paolo (c. 1460 or earlier)]] | |||

== Defending the Church == | == Defending the Church == | ||

| Line 24: | Line 26: | ||

In the Dialogue, the Father taught: when “the will of the soul unites itself with me in a most perfect and burning love” the soul “is another me, made so by the union of love.”<ref>Harvey Egan, ''An Anthology of Christian Mysticism'' (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, Pueblo Book, 1991), p. 361.</ref> “You will know me in yourself,” he told her, “and from this knowledge you will draw all that you need.”<ref>Mary Ann Fatula, ''Catherine of Siena’s Way'', rev. ed. (Wilmington, Del.: Michael Glazier, 1989), p. 80.</ref> | In the Dialogue, the Father taught: when “the will of the soul unites itself with me in a most perfect and burning love” the soul “is another me, made so by the union of love.”<ref>Harvey Egan, ''An Anthology of Christian Mysticism'' (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, Pueblo Book, 1991), p. 361.</ref> “You will know me in yourself,” he told her, “and from this knowledge you will draw all that you need.”<ref>Mary Ann Fatula, ''Catherine of Siena’s Way'', rev. ed. (Wilmington, Del.: Michael Glazier, 1989), p. 80.</ref> | ||

[[File:Domenico Beccafumi 071.jpg|thumb|Catherine of Siena receiving the stigmata, Domenico di Pace Beccafumi]] | |||

== The path of the mystic == | == The path of the mystic == | ||

Revision as of 07:27, 27 December 2020

Catherine of Siena (March 25, 1347–April 29, 1380) was an Italian mystic, defender of the pope and the Church. She was a previous embodiment of Elizabeth Clare Prophet.

Early life

At age six in a powerful religious experience Catherine saw the radiant figure of Christ the King raise his hand and bless her. He was seated on a throne, crowned with a mitre and surrounded by the apostles Peter, Paul and John. Believing that her vocation was to be in the world but not of the world, at age sixteen she became a Sister of Penance, a member of the Dominican third order who wears a habit but is not confined to a convent.

For the next three years Catherine remained cloistered in a small room in her father’s house, living a life of austerity, solitude and silence, withdrawing into the “inner cell” of the knowledge of God and self, as she described her communion with the Lord. She had many visions and conversations with Jesus, culminating in the spiritual marriage with Christ. During that time Catherine received Jesus’ teaching “I, nothing; God, All. I, nonbeing; God, Being.” This fundamental truth inspired in her the humility and the conviction that enabled her to confront the forces threatening the Church and society in the turbulent fourteenth century.

Defending the Church

At Jesus’ direction Catherine returned to public life in Siena, where she tended the poor and the sick. As her reputation for spirituality became known, there gathered around her a circle of devotees from all walks of life who called her their “sweet holy mother.” Catherine acted as a peacemaker and diplomat in order to bring peace to Italy and reform the Church. She traveled widely and addressed hundreds of letters to the prelates and sovereigns of the day, giving counsel and advice yet directly confronting misdeeds. Wherever Catherine went, preaching, teaching and healing, she brought a spiritual revival and led thousands of souls back to the Church.

In her absolute devotion to the papacy Catherine, accompanied by twenty-three devotees (friars, nuns and laymen), traveled to Avignon, France, where the popes had resided for the previous seventy years, in order to convince Pope Gregory to return the papacy to Rome. In 1377 the pope returned to Italy, but a year later with the election of his successor, Urban VI, certain cardinals set up a rival, or “anti-pope,” Clement VII. Thus began the “Great Schism,” which absorbed the remainder of Catherine’s life as she attempted to gain for Pope Urban VI the recognition that was rightfully his.

Final years

In November 1378 she moved to Rome to devote herself to the cause of the papacy. During the last months of her life Catherine went daily to Saint Peter’s basilica where she spent hours in prayer before the mosaic of “la Navicella,” the ship of the Church. Just before Lent in 1380 she had a vision of the ship being lifted out of the mosaic and placed upon her shoulders. Three months later, on April 29, 1380, at age 33, Catherine died, exhausted by her penances and efforts in the service of the pope and the Church. “O eternal God,” she had prayed upon her deathbed, “receive the sacrifice of my life for the sake of this mystical body of holy Church.”[1]

The Dialogue

Her greatest work, the “Dialogue,” a spiritual treatise in the form of conversations with God the Father, was dictated by Catherine to her secretaries during a five-day state of ecstasy. About four hundred of her letters have survived as well as twenty-six of her prayers.

In the Dialogue, the Father taught: when “the will of the soul unites itself with me in a most perfect and burning love” the soul “is another me, made so by the union of love.”[2] “You will know me in yourself,” he told her, “and from this knowledge you will draw all that you need.”[3]

The path of the mystic

Catherine understood the true meaning of imitating the life of Christ, and in 1375 she received the stigmata, which was visible only to herself, enabling her to share in Christ’s passion. At her request, they remained invisible until after her death.

Jesus taught Catherine that her bonding to him had to bear fruit not only for herself but for other souls as well. He said that she had to fly to heaven on “two wings”: “love of me and love of your neighbor.”[4]

For Catherine, “love of your neighbor” consisted of both action and intercessory prayer. “Let not a moment pass without crying out with constant prayer,”[5] God told her. One of Catherine’s recorded prayers reads:

Your Son is not about to come again except in majesty to judge.... But, as I see it, you are calling your servants christs, and through them you want to relieve the world of death and restore it to life.

How? You want these servants of yours to walk courageously along the Word’s way with concern and blazing desire, working for your honor and the salvation of souls....

O best of remedy-givers! Give us then these christs who will live in continual watching and tears and prayers for the world’s salvation. You call them your christs because they are conformed to your only-begotten Son.[6]

Thus Jesus revealed to Catherine that there must be many Christs. We are all Christs in potential. And the level to which our Christ is seated in the body where we sit entirely depends upon each of us and what action we take from this profound understanding.

The mystical path is truly a practical path. It is practical because we learn how to contact God and find our way back to his heart. It is practical because it deals with the needs of the hour on planet Earth.

Legacy

In recognition of her “infused wisdom,” an “inebriating assimilation” of the mysteries of sacred scripture, Pope Paul VI proclaimed Saint Catherine of Siena a Doctor of the Church on October 4, 1970. The teachings of this Angelic Doctor are revealed in her hundreds of letters addressed to kings, popes, abbots, theologians, and soldiers during the turbulent fourteenth century as well as in the excellence of her life as “one of the most vigorous and virile women in history.”

Catherine was canonized in 1461; she was declared the patron saint of Italy in 1939. Her feast day is celebrated on April 30.

Sources

Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 31, no. 46.

Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 23, no. 41, October 12, 1980.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, June 28, 1992, “Roots of Christian Mysticism.”

- ↑ Edmund G. Gardner, Saint Catherine of Siena: A Study in the Religion, Literature, and History of the Fourteenth Century in Italy (London: J. M. Dent, 1907), p. 343.

- ↑ Harvey Egan, An Anthology of Christian Mysticism (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, Pueblo Book, 1991), p. 361.

- ↑ Mary Ann Fatula, Catherine of Siena’s Way, rev. ed. (Wilmington, Del.: Michael Glazier, 1989), p. 80.

- ↑ Raymond of Capua, The Life of Catherine of Siena, trans. Conleth Kearns (Wilmington, Del.: Michael Glazier, 1980), p. 106.

- ↑ Catherine of Siena, The Dialogue, trans. Suzanne Noffke (New York: Paulist Press, 1980), 32.

- ↑ The Prayers of Catherine of Siena, ed. Suzanne Noffke (New York: Paulist Press, 1983), pp. 178, 179.