Tibet

Tibet is situated on a plateau the size of Western Europe in the heart of Asia. Its average altitude is fifteen thousand feet. It is majestically surrounded by the world’s highest mountains, including the Himalayas.

Once an independent and predominately Buddhist nation ruled by the Dalai Lama, who acted as both spiritual and temporal head, Tibet was invaded by the Communist Chinese in 1950.

The significance of religion in Tibet

In order to understand Tibet one must understand its religion—for the two are virtually inseparable. This passage from an eighth- or ninth-century Tibetan text describes how heaven and earth are one in the land and hearts of the people of Tibet:

- This center of heaven,

- This core of the earth,

- This heart of the world,

- Fenced round by snow,

- The headland of all rivers,

- Where the mountains are high and

- The land is pure.

This is the meeting place of the etheric and physical octaves in the East. The Inner Retreat and the Western Shamballa is the Place Prepared and chosen in the West for that very phenomenon of the merging of the etheric and physical octaves. The physical and the etheric are connected at the heart of the chela. At the point of the heart and the expansion of the threefold flame of the Three Jewels of the Buddha, the Dharma, the Sangha, there we find that the etheric octave may descend and be in the physical earth for the beginning of the days when the golden age will come and earth shall be raised again to the etheric octave.

The coming of Buddhism

The recorded history of Tibet begins in the seventh century. The most important ruler of the time was Tibet’s thirty-third king, Songtsen Gampo (A.D. 609 to 649). He married two princesses—one from China, the other from Nepal. They were both Buddhists and are credited with introducing Buddhism into Tibet.

Buddhism did not gain a strong foothold in Tibet until the reign of King Trisong Detsen, who was the first to establish the new faith in place of the traditional practice of the Bon religion. The Bon religion totally denies that Gautama Buddha is the Buddha of our age.

Because the King’s plan to restore Buddhism were being vehemently opposed by the Bon-po, in A.D. 746 to 747 he asked the Indian adept Padma Sambhava to come to his land to defeat these forces.

Padma Sambhava

► Main article: Padma Sambhava

Although much of the life and work of the “Precious Guru,” as Padma Sambhava is called, is obscured in legend, we do know that he was a teacher at the great monastic university at Nalanda, India. He was famed for his mystical powers and mastery of the occult sciences.

The adept was able to exorcise demons who were opposing the building of the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet, Samye, and under royal patronage he converted the country to the Nyingma school of Buddhism. He supervised the completion of the monastery, and in 767 the first Tibetan Buddhist monks were ordained—seven in number. Padma Sambhava, whose name means “lotus born,” is thus revered as the founder of Tibetan Buddhism.

Having achieved success over the Bon-po, King Trisong Detsen now granted Buddhist monks a high status above lay authorities, a tradition that became a characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism.

Padma Sambhava is said to have made prophecies concerning the future of Tibet which are seeing their fulfillment in this day. One prophecy attributed to Padma Sambhava is this:

When the iron bird flies and the horses run on wheels, the Tibetan people will be scattered like ants across the face of the earth, and the Dharma will come to the land of the red men.[1]

One Tibetan manuscript contains the following prophecy of Padma Sambhava, which is said to have been voiced through a lama in the seventeenth or eighteenth century:

In the time of sinful, soiled, and corrupt custom—in the future—the demons and spirits of the Planets will infest the world. At that time, the Demon King Pehar will be very powerful and dominant [his teachings will spread afar]. Because of the powerful influence of the Demon King Pehar, the cases of insanity and nervous disturbance will be many, the cases of violent death will also be great in number....

At that time half of the populations [of all nations] will become insane; most of the people will cut short their own lives by themselves (suicide); and at that time China will become a dark land. Powerful men and wealth will follow the steps of the evil spirits and their three cousins; all Tibet will be broken into small pieces. At that time, here in the Snow Country, the life and breath of the lamas, the officials, the teachers, the kings, the high officers, and those who follow the Buddhist teachings will be taken away (and persecuted). All the good teachers and virtuous persons will be cut in the middle by the evil demons. People will suffer excessively.[2]

The growth of Buddhism

In the eleventh century the Indian monk Atisa came to Tibet and greatly influenced the growth of Buddhism based on monastic discipline, stressing devotion to Avalokitesvara and the path of the bodhisattva.

In the eleventh and twelfth centuries several new schools of Buddhism were founded, including the Kagyupa school, brought to Tibet by Marpa, which emphasized meditative procedure and yogic powers. Marpa’s most famous disciple was Milarepa.

As a result of the resurgence of Buddhism in the eleventh century, government power rested largely with the monasteries. As Pratapaditya Pal writes in Art of Tibet:

Translating and organizing the religious literature and founding monasteries and religious orders seem to have been the principal occupations of the Tibetans from the tenth to the thirteenth century.... Most major monasteries and religious orders of Tibet were founded in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.[3]

From the thirteenth to the eighteenth century, Tibet came under Mongolian influence. In the thirteenth century, Kublai Khan, emperor of China, made Lamaism the national religion of the Mongolian Empire. Thereafter, lamas of the Sakya sect ruled Tibet as a theocracy for several centuries.

Establishment of the Yellow Hat school

The last and most important school in Tibetan Buddhism was founded in the fifteenth century by Tsong-kha-pa, who established his monastery close to Lhasa. This school, originally called the “Followers of the Way of Virtue,” was dubbed the “Yellow Hats” by Western writers. It emphasized the ideals of monastic discipline, including celibacy and abstention from intoxicants.

Per Kvaerne writes in The World of Buddhism:

In 1408 Tsong-kha-pa instituted the annual New Year celebration, called the Great Prayer, in the ancient Jokhang temple in Lhasa, intending it as a yearly rededication of Tibet to Buddhism. Thereafter, the Great Prayer continued every year without interruption until 1959.[4]

Since the seventeenth century, the Yellow Hats have been the predominant Buddhist order in Tibet. This is the order to which the Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas belong. The Dalai Lama is regarded as an incarnation of [[Avalokitesvara], and he was the spiritual and temporal ruler of Tibet. The Panchen Lama is venerated as the spiritual representative of the Dalai Lama and is regarded as the incarnation of the Buddha Amitabha.

Up until the Communist takeover, monasteries were the hub of Tibetan life. A large percentage of the country’s adult male population were monks.

The Dalai Lama

Tibetan Buddhists believe that each Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama is a reincarnation of the previous Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama. Pal writes:

The concept of guru, which originated in India and was transplanted into Tibet, became influenced by the sense of hierarchy that is fundamental to Tibetan social morphology, and, in the institution of the lama, achieved an unprecedented preeminence. The emphasis on lineage, as well as on emanation in the form of the tulku, is likewise characteristically Tibetan, though these concepts are not unknown in India.

A tulku is generally regarded as a “reincarnated lama” or “a living Buddha.” It is believed that when an enlightened teacher or religious personage passes away, he is reborn in another body. The Dalai Lama is perhaps the best-known example of a tulku. When a Dalai Lama dies, a special search is conducted to find his successor; invariably, he is a young boy but is said to be the dead Dalai Lama’s reincarnation. Inasmuch as Buddhism does not believe in the existence of the soul, there is an inherent contradiction in the use of the words reincarnation or rebirth; that is why the expression “emanation” is perhaps more suitable.[5]

In other words, it is the emanation of the individual that reincarnates. In this we find the concept of the essence or the breath that we would term “soul,” even though this term is not used by Buddhists.

In any event, because of the particular emphasis given to the concept of tulku, especially after the sixteenth century, every important religious figure in every monastery traced his lineage through spiritual forebears, to mahasiddhas, and ultimately to various divinities. Thus, the Dalai Lama is an emanation not only of various earlier saints or teachers but also of the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara.[6]

One Tibetan refugee describes what the Dalai Lama means to the Tibetan people:

The connection of every Tibetan with the Dalai Lama is a deep and inexpressible thing. To us, the Dalai Lama symbolizes the whole of Tibet: the beauty of the land, the purity of its rivers and lakes, the sanctity of its skies, the solidity of its mountains, and the strength of its people. Even more, he is the living embodiment of the eternal principles of Buddhism, and also the epitome of what every Tibetan, from the most debauched harlot in Lhasa to the saintly ascetic, is striving and longing for—freedom, the total freedom of Nirvana.[7]

In this we glean that the Dalai Lama, representing the Guru, the Buddha, embodies the spirit of Tibet and all of its people and all of its history. In the person and the face, then, of the Guru, of the Dalai Lama, the people see all of this, and their adoration is of something far beyond the physical form. and yet it includes that form as the temple of the Buddha.

China and Tibet

In the seventeenth century, when the Manchus came to power in China they assumed nominal control of Tibet, but Tibet remained essentially a self-ruling theocracy with the Dalai Lama at its head. With the opening of the twentieth century, Tibet was faced with major political challenges. Twice, in 1904 and 1910, the Dalai Lama was forced to flee into exile. The second exile came when the Manchus invaded Tibet and tried to take control of the country.

In 1911, when the Manchus were toppled by the Chinese revolution, they lost control of Tibet, and the Dalai Lama was able to return to Lhasa in 1913. With China embroiled in its own internal struggles between warlords followed by a civil war between the Nationalists and Communists, Tibet enjoyed a period of peace and independence.

The prophecies of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama

However, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama saw the handwriting on the wall. He tried to warn his people of the coming darkness from without and he warned them to prepare from within. In 1932 he released his final testament to the people of Tibet in what has come to be known as “The Prophecies of the Great Thirteenth.” His message read in part:

Our two most powerful neighbours are India and China, both of whom have very powerful armies. Therefore we must try to establish amicable relations with both of them. There are also a number of smaller countries near our borders [who] maintain a strong military. Because of this it is important that we too maintain an efficient army of young and well-trained soldiers, and are able to establish the security of the country....

If we do not make preparations to defend ourselves from the overflow of violence, we will have very little chance of survival. In particular, we must guard ourselves against the barbaric Red Communists, who carry terror and destruction with them wherever they go. They are the worst of the worst. Already they have consumed much of Mongolia, where they have outlawed the search for the reincarnation of Jetsun Dampa, the incarnate head of the country.

They have robbed and destroyed the monasteries, forcing the monks to join their armies or else killing them outright. They have destroyed religion wherever they’ve encountered it, and not even the name of Buddhadharma is allowed to remain in their wake....

It will not be long before we find the Red onslaught at our own front door. It is only a matter of time before we come into a direct confrontation with it, either from within our own ranks or else as a threat from an external (Communist) nation. And when that happens we must be ready to defend ourselves. Otherwise our spiritual and cultural traditions will be completely eradicated. Even the names of the Dalai and Panchen Lamas will be erased, as will be those of other lamas, lineage holders and holy beings.

The monasteries will be looted and destroyed, and the monks and nuns killed or chased away. The great works of the noble Dharma kings of old will be undone, and all of our cultural and spiritual institutions persecuted, destroyed and forgotten. The birthrights and property of the people will be stolen. We will be become like slaves to our conquerors, and will be made to wander helplessly like beggars. Everyone will be forced to live in misery, and the days and nights will pass slowly, and with great suffering and terror.

Therefore, now, when the strength of peace and happiness is with us, while the power to do something about the situation is still in our hands, we should make every effort to safeguard against this impending disaster. Use peaceful methods where they are appropriate; but where they are not appropriate, do not hesitate to resort to more forceful means. Work diligently now, while there is still time. Then there will be no regrets....

One person alone cannot ward off the threat that faces us; but together we can win out in the end. Avoid rivalry and petty self-interests, and look instead to what is essential. We must strive together with positive motivation for the general welfare of all, while living in accordance with the teachings of the Buddha.

If we do this, then there is no doubt that we will abide within the blessings of the national protective divinity Nechung, who was appointed by the Acharya (Padma Sambhava) to assist the line of Dalai Lamas in the task of caring for Tibet.... Think carefully about what I have said, for the future is in your hands. It is extremely important to overcome what needs to be overcome, and to accomplish what needs to be accomplished. Do not confuse the two.[8]

Reports by Nicholas Roerich

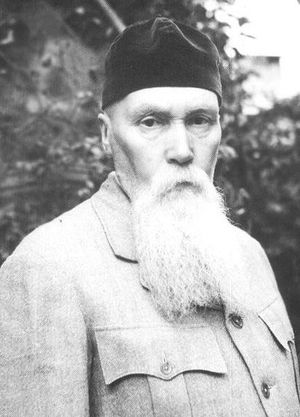

Prior to the Thirteenth Dalai Lama’s passing, Professor Nicholas Roerich led an expedition to Tibet and several other regions of Central Asia between 1924 and 1928. He made the following observations as reported in the New York Times of June 11, 1928:

A depressing picture of the economic, political and sanitary conditions in Tibet is drawn in the statement made by Professor Nicholas Roerich, Russian painter and archaeologist.... Roerich believes that the influence of [the] Dalai Lama is fast waning, with all Tibet rapidly splitting into factions.

In subsequent months, the New York Times reported:

Nicholas Roerich, whose first purpose was to obtain paintings of Tibetan life, brought back no picture more striking than his account of the moral, physical and religious degradation of a dying race. He states that the “black faith of Bon Po,” most ancient of the pagan religions, is spreading all over Tibet. The decline of Buddhism in Central Asia, he said, had been accompanied by ancient demon-worshipping rites.

The Times also quotes a letter written by Roerich about Tibet in which he said: “Here are high Lamas who, on their sacred beads, are calculating their commercial accounts, occupied completely with thoughts of profit.” The article continues: “The Lamas also beg and indulge in dishonest methods to get money from others, the letter sets forth. Many monasteries, the writer said, are in ruins.”[9]

1933 to 1950

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama died in 1933. In the years following his passing, Tibet was beset by factionalism and internal conflicts, including periods when bribery and bureaucratic negligence were rampant. In addition, a delegation of Chinese Nationalists was allowed into the country under the pretext of a condolence mission. But instead of leaving when their official business was completed, they set up a permanent liaison office.

As author John Avedon writes in his study of the Chinese occupation called In Exile from the Land of Snows, fifteen years after the arrival of the Chinese mission,

Their attempts at subterfuge had grown to include Tibetans in all segments of society. It was not until July 1949 that the Tibetan government realized the extent of the infiltration and, fearful that the newly victorious Communists would take advantage of it, closed the “liaison’ office, deporting its staff, along with some twenty-five known agents and their Tibetan accomplices....

On New Year’s Day 1950, just three months after the formation of the People’s Republic of China, Radio Peking announced to its people and the world that “the tasks for the People’s Liberation Army for 1950 are to liberate Taiwan, Hainan and Tibet.”[10]

However, the Tibetans were unable to face the prophecies of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama and the threat of Chinese Communist invasion. An eyewitness who experienced firsthand the events in Lhasa prior to the takeover explained that as the threat of invasion grew,

It seemed as if the entire population of Tibet had packed the narrow streets of Lhasa in pious enthusiasm for the religious festivals which in 1950 surpassed in pomp and splendor anything I had ever seen. Despite the threat from the Chinese, the ceremonies vital to the running of the state had to continue. Four weeks after the great New Year festival, the twenty thousand monks of the monasteries around Lhasa descended once again into the city for the second prayer festival. The people believed with rocklike faith that the power of religion would suffice to protect their independence.

The main event of the second prayer festival was the chastisement of evil spirits. The full force of the tantric order was mobilized. In front of the central cathedral the abbots of the great monasteries were challenged to throw dice to decide the fate of Tibet. Two scapegoats symbolizing evil were the challengers. Representatives of the Tibetan government supervised the contest. They took no chances. The dice were loaded—the faces of the abbot’s dice all marked with sixes, those of the demons with ones. The moment ritual victory was won for Tibet, the scapegoats were driven from the town. The prayers ended with a great procession to the foot of the Potala Palace.[11]

Chinese takeover

On October 7th, 1950, the Communists invaded Tibet with 84,000 troops, claiming they had come “to liberate the oppressed and exploited Tibetans and reunite them with the great motherland.”

Tibet had a glorified border patrol of some 8,500 troops, only fifty pieces of artillery and a few hundred mortars and machine guns, and the People’s Liberation Army quickly defeated the Tibetans. On November 17th, 1950, the new Dalai Lama was invested as supreme temporal ruler of Tibet at the age of fifteen.

On May 23rd, 1951, without any authority from the Dalai Lama or his cabinet, Tibetan delegates signed a seventeen-point agreement for the “peaceful liberation of Tibet.” In it Tibet agreed “to return to the big family of the Motherland—the People’s Republic of China”—in return for the guarantee that the central authorities would not “alter the existing political system in Tibet” or “the established status, functions, and powers of the Dalai Lama.”

As author Steven Batchelor summarizes the events of these years:

The Tibetans were ill-prepared to cope with this invasion, and with a minimum of resistance the Chinese army made its way into Lhasa in September 1951.

The Chinese arrived on a wave of optimistic promises and good-will with which they tried to win the Tibetans over to the idea of a just and equal socialist society.

The Dalai Lama’s government tentatively agreed to cooperate with a number of measures aimed at improving the Tibetans’ lot by introducing certain features of modern life, such as roads and electricity. This uneasy alliance did not last long. Suspicious of the communists’ motives, the Khampas in Eastern Tibet staged a revolt in 1956 that soon became a full-scale insurrection.[12]

Avedon writes of this period:

Though by some accounts the Chinese lost forty thousand soldiers between 1956 and 1958, their campaign in Kham—as attested to in two reports (issued in 1959 and 1960) by the International Commission of Jurists, a Geneva-based human rights monitoring group comprised of lawyers and judges from fifty nations—let loose a series of atrocities unparalleled in Tibet’s history.

The obliteration of entire villages was compounded by hundreds of public executions, carried out to intimidate the surviving population. The methods employed included crucifixion, dismemberment, vivisection, beheading, burying alive, burning and scalding alive, dragging the victims to death behind galloping horses and pushing them from airplanes; children were forced to shoot their parents, disciples their religious teachers.

Everywhere monasteries were prime targets. Monks were compelled to publicly copulate with nuns and desecrate sacred images before being sent to a growing string of labor camps in Amdo and Gansu. In the face of such acts, the guerrillas found their ranks swollen by thousands of dependents, bringing with them triple or more their number in livestock. So enlarged, they became easy targets for Chinese air strikes. Simultaneously, the P.L.A. threw wide loops around Tibetan-held districts, attempting to bottle them up and annihilate one pocket at a time. The tide of battle turning against them, a mass exodus comprised of hundreds of scattered bands fled westward, seeking respite within the precincts of the Dalai Lama.[13]

Following the revolt in Kham, Batchelor relates:

Tensions mounted in Lhasa and an armed resistance movement was soon active in Central Tibet. In March 1959 the general of the Chinese forces in Lhasa made an unusual request for the Dalai Lama to attend a theatrical show inside the Chinese military base. This was immediately interpreted by the Tibetans as a ploy to kidnap their leader, and they reacted with a series of popular demonstrations in Lhasa and outside the Norbulingka, the grounds of the Dalai Lama’s summer palace.

This explosive confrontation finally erupted on March 17th. The Chinese started shelling the city and that evening the Dalai Lama and his entourage fled south in the direction of India. The demonstrations turned into an outright rebellion against the unwanted Chinese presence in Tibet that was met with full fury of the Chinese military. Fierce fighting broke out in Lhasa but the superior Chinese forces quickly overwhelmed the Tibetans, inflicting heavy casualties and damaging many buildings. From now on the Chinese dropped any pretense of “peaceful liberation” and set out to incorporate Tibet into the People’s Republic of China.[14]

Destruction of Tibetan culture and religion

After the Dalai Lama left Tibet, crackdowns on Buddhism became more severe. All monasteries which participated in the uprising were dismantled and authorities took over the monastic properties. The monks were sent to labor camps. “Struggle meetings” were organized throughout Tibet. In meetings, leading abbots connected with the rebels were accused and denounced.

At Depung, the largest monastery in the world, monks were confined to the monastery for two weeks. Those judged to be “reactionaries” were brought to mass meetings where they were denounced and then publicly executed. Only elderly monks could stay as caretakers of the monastery.

Monasteries were destroyed. Small stupas and temples were dismantled. The Chinese systematically destroyed the highly revered group of temples of the Goddess Tara. Public worship was thus made impossible. Private worship was discouraged and even ridiculed but was still possible.

The Chinese instituted thamzing, which means reform through struggle. Everyone had to attend struggle meetings. Members of the old order, lamas and landlords, had to undergo thamzing, which often resulted in physical violence. People from lower orders who didn’t denounce their former masters with enough enthusiasm were also subjected to thamzing.

At one meeting an organizer said, “The meeting will not stop until the whole audience denounces the Dalai Lama.... Everyone had to say, ‘The gods, lamas, religion and monasteries are tools of exploitation.... The Chinese Communist Party liberated us.... The Chinese Communist Party is more kind than our own parents.’”[15]

But all of this was only the beginning. The Cultural Revolution was the true era of the destruction of Tibetan religion and culture. It was Mao’s attempt to wipe out conservative and moderate elements in the Communist Party and the government. It was to be a violent “cleaning” of China’s “rotten core.” During it, the “Four Olds”—old ideology, old culture, old customs, and old habits—were to be destroyed.

Many Tibetan youths participated, particularly those who had received a Chinese secondary education. In Tibet, Buddhism became the primary object of the destruction campaign. The Jokhang Temple was Tibet’s holiest shrine. Built in the seventh century, it was the Mecca of Buddhism for many Buddhists throughout Asia. On August 25th, 1966, Red Guards invaded and destroyed it and defaced hundreds of priceless frescoes and images. For five days its courtyards were filled with mobs burning scriptures. After the rampage it was renamed Guest House number 5. The main temple was used as a pigsty. Its catacombs were taken over for the most radical Red Guard troops.

Within a few days the destruction moved to Lhasa. Street plaques were smashed and given revolutionary titles. During the first week in September, forty thousand copies of Mao’s portrait were distributed in Lhasa and placed over every gate, in every home, office and factory. Giant red posters were put on the Potala Palace and elsewhere. Six thousand monasteries—almost all of the monasteries in Tibet—as well as most of the remaining temples and historic buildings were destroyed.

During the Cultural Revolution, Tibetan culture suffered a fatal blow. Everything Tibetan was destroyed; everything Chinese and Communist was adopted. The practice of religion was officially outlawed in Tibet. Folk festivals and fairs were banned. All Tibetan art forms, traditional dances and songs, and customs were prohibited. Distinctive black borders framing windows and bright colors in rooms were painted over. In Kham and Amdo provinces, second floors were razed and people forced to live in damp, windowless stables on the first floor. The long plaits of hair traditionally worn by men and women were labeled “the dirty black tails of serfdom.” If people didn’t cut them off, Red Guards slashed them off.

By March 1967 tens of thousands of copies of Mao’s Little Red Book were given out. Tibetans were required to memorize passages and were tested in nightly meetings by the Red Guard, who demanded flawless recitation on pain of violence. The traditional Tibetan greeting was forbidden. Private pets were exterminated by Red Guards. Tibetans were forced to hang portraits of Mao in every room. Tibetan youths were marshaled into pet and insect extermination campaigns to counter Tibetans’ abhorrence of taking life.

Tibetan writing and language were replaced by “Sino-Tibetan Friendship Language,” whose grammar and vocabulary was incomprehensible to Tibetans. Many Tibetans were forced to change their names to Chinese equivalents, each with one syllable of Mao’s name included. When parents resisted naming their offspring for Mao, children were officially called by their date of birth or their weight at birth.

During the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese committed unspeakable atrocities against the Tibetans. People were branded with hot irons. They were subjected to executions and impromptu thamzing in the street. There were gang rapes. The female children of four hundred families were marched naked in public by the Red Guard, submitted to thamzing, then raped.

During winter, women were stripped, bound, and made to stand on frozen lakes under guard. A man and daughter were forced to copulate in public. Tibetans were left tied in gunnysacks for days. Families were made to stand in freezing water for five hours wearing dunce caps, with heavy stones strapped to their legs. Tibetans committed suicide, sometimes in family groups, by leaping from cliffs or drowning to avoid dying at Chinese hands.

The Chinese carried out a calculated policy of cultural genocide during the Cultural Revolution. One of their key objectives was the destruction of religion. They carefully planned the annihilation of monasteries even prior to the Cultural Revolution. In 1959, the Cultural Articles Preservation Commission began cataloging every item in every monastery for eventual shipment to China.

In 1967 the destruction of monasteries began in earnest. Local Tibetans were forced to do the work. Images of gold, silver and bronze, expensive brocades, and ancient tankas were packed and shipped to China. Intricately carved pillars and beams were taken out of the monasteries and were used to build Chinese compounds. Thousands of scriptures were burned in giant bonfires. Scriptures that were not burned were desecrated—they were used for toilet paper, shoe padding, and wrapping paper. Clay images were ground to dust and thrown into the street or mixed with fertilizer. Others were made into bricks specifically to build public lavatories. Mani stones were turned into pavement. Frescoes were defaced. Pinnacles of bronze and gold which crowned temples were melted down. After the monasteries were pillaged, the buildings were dynamited.

Samye monastery, which was built by Padma Sambhava in the eighth century and was regarded as one of the holiest pilgrimage spots in Tibet, was completely destroyed. The act of desecrating a monastery had a devastating psychological effect on those forced to do it. At Nuplung, a hamlet near Central Tibet, villagers were ordered to dismantle the local monastery and stupa. Scriptures from the stupa were mixed with manure and spread on the fields. People were crying and fainting. The caretaker went crazy.

The Chinese have more recently permitted the limited worship and practice of Buddhism in Tibet. But the Dalai Lama has said that because of “direct and indirect restrictions on the teaching and study of Buddhist philosophy,” Buddhism is “being reduced to a blind faith.”[16]

Destruction of the Tibetan people

The Chinese occupation debilitated Tibetan agriculture and caused the onset of a severe famine that lasted from 1968 to 1973.

In 1970 the Chinese began a “class cleansing campaign.” It affected all segments of society. Tens of thousands of Tibetan cadres who were working for the Chinese government were removed from the bureaucracy. Thousands were arrested at nighttime raids, taken to prisons, and questioned. Executions were held on large public meeting grounds. Families of those to be executed were assembled at the head of the crowd. They were made to applaud and were forced to thank the Party for its “kindness” in eliminating a “bad element.” Their loved ones were executed by a bullet to the back of the head. Then they had to bury the warm and bloody corpse in an impromptu grave without covering it. Finally, they were charged five dollars for the bullet.

After consolidating control in Tibet, the Chinese also undertook a massive population transfer, encouraging Chinese citizens to emigrate to Tibet by offering them triple salary and other benefits in an effort to make Tibetans a minority in their own country. In 1987 it was reported that there were 7.5 million Chinese occupying a country of 6 million Tibetans.[17] In the 1960s, the Chinese began a campaign of involuntary sterilization of Tibetans. Gradually this method was phased out in favor of inducing Tibetan women to marry Chinese soldiers.[18]

Since they invaded Tibet in 1950, the Red Chinese armies have killed more than 1.2 million Tibetans.[19] Since many of those murdered were members of the intelligentsia, such as monks and teachers, Tibet’s cultural heritage is not being passed on to the next generation. “For the first time in Tibet’s history, there is a ‘lost generation,’” writes John Avedon. “They’re bitter, depressed and, with all opportunity denied them, lazy.”[20] “A 2,000-year-old civilization was essentially destroyed in a mere 20 years.”[21]

U.S. government reaction

Since 1978, the United States government has held that Tibet is a part of China and has given only token support to the Tibetan people.

In late September 1987, reports filtered out of Tibet that hundreds of Buddhist monks had staged peaceful protests calling for Tibetan independence. These protests coincided with the Dalai Lama’s visit to the U.S., during which he presented a 5-point peace plan to the Congressional Human Rights Caucus. The House passed a resolution supporting him, and leading members of the Congress sent a letter urging China’s premier to use the 5-point program as a basis of negotiation with the Dalai Lama.

The Chinese responded on September 24 by gathering 15,000 Tibetans at a stadium in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet, sentencing eight to prison and two to death, and executing one immediately. In this they demonstrated their utter disdain for the United States government and Congress. On October 1, thousands of Tibetans demonstrated in Lhasa and Chinese police fired AK-47 assault rifles into the unarmed crowd, killing at least 12.

The Senate voted to condemn China for the crackdown, but the Reagan administration actually voiced support for China, even though it later backpedaled. On October 6, the State Department announced its strong opposition to the Senate move. The New York Times reported that “one State Department official said that any possible benefits of the Senate action for the Tibetan people were ‘insufficient to outweigh the almost certain damage to the United States-China bilateral relationship.’”[22] That relationship is based primarily on trade and Western capitalists foreseeing great profits in Chinese markets.

Since that time the United States government has been only too willing to accept the false liberation of Tibet and to ignore human rights violations in the interests of trade.

The karma of Tibet

The Elohim Heros and Amora commented in 1989 on the destruction of the people of Tibet and their culture:

Let there be, then, the understanding that protection to earth can come only through spiritual and physical defense. That is evident, beloved, where the people of Tibet did not desire to know the dire prophecy at hand but preferred the loaded dice. So I say, recognize that spiritual protection is not enough. And yet by the science of the spoken Word the spiritual protection you invoke does coalesce as physical protection when you do the work to manifest that physical protection yourselves!

And I must say, you are far more practical in this regard than your counterparts in Lhasa. They have learned [their lesson] all too late, far too late, beloved. And thus, they have no guaranteed right to bear arms and no clear religious directive to do so, whereas the Constitution does guarantee to the American people the right to [keep and] bear arms.[23]

And as one disciple commented, the most notable lesson of Tiananmen Square, as you would observe, is that all of the arms were in the hands of the army and the government.[24] And the citizens were bereft of any means of self-defense against a government that would turn against its citizens and turn its armies against its citizens. Consider the wisdom of the Founding Fathers, that you might be guaranteed defense against a government gone mad and an army of automatons following [their madness]. Recognize, beloved, that those students had not advanced in their astuteness to realize that it is the entire Bill of Rights and the entire Constitution that does guarantee and safeguard the independence of every individual citizen.

Therefore know, beloved ones, that that right was not exercised in Tibet as admonished by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. Instead [of entering a path of heightened self-discipline], the people became corrupt in his absence, turned in upon themselves in their self-indulgences, and did not take those years from 1933 forward to prepare themselves for their Armageddon.

Blessed are they who have suffered in the name of Buddha, for they who have suffered in the name of the Buddha shall receive the Buddha’s reward. Yet the refiner’s fire[25] has come to them. They had not the call to Astrea nor the violet flame. Therefore they too must meet [the karma of] even that level of disobedience to their leader which brought them to that point of vulnerability.

Blessed ones, I do not imply that there is a heavy karma on the part of Tibetans, for this is a karma [that was] initiated [by] Communist hordes for which they themselves shall be judged. And yet, beloved, by 1950 the teachings of the ascended masters and of the Great White Brotherhood had been well installed in the west for almost a century.

Therefore understand, the Dalai Lama is a highly educated man who does know the way of the West. Realize that any ignorance, beloved, any ignoring of the impulsations of the light from on high, by whatever neglect or density, does create its own karma. As they say, ignorance of the Law is not an excuse.

It is tragic, beloved. It is tragic that many who are the male leaders in spiritual fields, although in the East they anticipate the coming of the World Mother, have not received her teaching through the ascended masters and the messengers, have not seen her, though her coming in the West is prophesied, though Tara is seen as descending all in white! Indeed, the prophecies have been written, they have been given. But as we say, karma blinds. But so does tradition outworn! So does a doctrine not of God but of man.

But, beloved hearts, let us not lay [the entire burden of guilt] at the feet of those who are in one sense victims and [most certainly] sincere [in their motives]. Let us lay it where it belongs, at the feet of the fallen angels who have traduced [those who would be the true followers of God[26]] again and again by the distortion of the teachings of Sanat Kumara.

Blessed ones, how can this happen? I tell you, they become lost in their scriptures and textbooks. And they have not the key of light, and they have not put together the essential Truth that is the portion of the Mother to give you, the synthesis of the teaching of the great laws and dispensations [of the Lord of the World and the Cosmic Christ] and [how] to apply them to the present moment.[27]

Pray for the Tibetans

Time after time after time El Morya has made the plea, “Pray for the Tibetans. They are my chelas. They are the devotees of the Buddha. Pray for them.”[28]

Sources

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, July 5, 1989.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, “The Abdication of America’s Destiny,” Part 2, Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 31, no. 23, June 5, 1988.

Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 32, no. 43, October 22, 1989.

- ↑ Lama Govinda, The Lost Teachings of Lama Govinda: Living Wisdom from a Modern Tibetan Master (Wheaton, Ill.: Quest Books, 2007), p. xviii. The “land of the red men” may refer to North American continent and the American Indians.

- ↑ C. A Muses, eds., Esoteric Teachings of the Tibetan Tantra, chapter 2, found online at http://www.sacred-texts.com/bud/ettt/ettt03.htm. For an account of the disasters that were prophesied to befall Tibet during the middle of the Kali Yuga (the last and worst of the four world ages), including an invasion by China, the destruction of monasteries, and desecration of sacred scriptures, see also the teachings of Padma Sambhava in The Legend of the Great Stupa (Berkeley: Dharma Publishing, 1973), pp. 15–16, 49–59.

- ↑ Pratapaditya Pal, Art of Tibet: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection (Los Angeles, Calif.: The Museum; Berkeley: in association with University of California Press, 1983), p. 25.

- ↑ Per Kvaerne, “Tibet: The Rise and Fall of a Monastic Tradition,” in Heinz Bechert and Richard F. Gombrich, eds., The World of Buddhism: Buddhist Monks and Nuns in Society and Culture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1984).

- ↑ Pal, Art of Tibet, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 38.

- ↑ Aten Doghya Tsang, quoted in “The Dalai Lama: The lost horizons,” The Guardian, May 7, 1999. https://www.theguardian.com/books/1999/may/08/books.guardianreview9

- ↑ Glenn H. Mullin, “The Great Thirteenth’s Last New Year Sermon,” Tibetan Review 22 (October 1987): 17.

- ↑ New York Times, August 22, 1928.

- ↑ John F. Avedon, In Exile from the Land of Snows (New York: Vintage Books, 1986), pp. 26–27.

- ↑ BBC documentary Tibet: The Bamboo Curtain Falls.

- ↑ Stephen Batchelor, The Tibet Guide (London: Wisdom Publications, 1987), p. 32.

- ↑ Avedon, In Exile, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Batchelor, Tibet Guide, p. 32.

- ↑ Dhondub Choedon, Life in the Red Flag People’s Commune (Dharamsala, india: The Office, 1978), p. 60.

- ↑ “Documentation,” News Tibet, September-December 1987, p. 3.

- ↑ “Stand Up for Decency in Tibet,” New York Times, October 8, 1987.

- ↑ Avedon, In Exile, pp. 266–67.

- ↑ John F. Avedon, “The U.S. Must Speak Up for Tibet,” New York Times, October 10, 1987.

- ↑ John F. Avedon, “Tibet Today: Current Conditions and Prospects,” p. 12.

- ↑ John F. Avedon, “Tibet Today,” Utne Reader, March/April 1989, p. 36.

- ↑ Elaine Sciolino, “Beijing Is Backed by Administration on Unrest in Tibet,” New York Times, October 7, 1987.

- ↑ The Second Amendment of the Constitution of the United States of America states that “a well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.”

- ↑ After seven weeks of peaceful protests in and mass occupation of Tiananmen Square by Chinese students and their supporters demanding greater freedoms, on June 4, 1989, the Chinese government sent thousands of troops from the 27th Army into the square behind armored personnel carriers and tanks. The soldiers turned on their fellow countrymen with tear gas and automatic rifles and charged the demonstrators with bayonets. The unarmed civilians could only respond with stones or Molotov cocktails. It is estimated that when the massacre was over as many as 3,000 to 7,000 were killed.

- ↑ Mal. 3:1–3.

- ↑ Eph. 5:1.

- ↑ Heros and Amora, “The Chalice of Your Heart,” Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 32, no. 43, October 22, 1989.

- ↑ Elizabeth Clare Prophet, May 4, 1991.