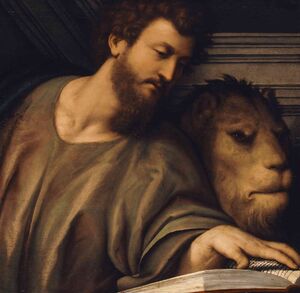

Saint Mark

Mark the Evangelist was an earlier embodiment of Mark L. Prophet, now the ascended master Lanello.

Mark is known as the probable author of the second gospel, the “Gospel of Deeds,” whence comes the symbol of Mark the Evangelist as a winged lion—the second “living creature” beheld by Ezekiel in his vision of the glory.[1]

He was raised an Essene and, being well-educated, was chosen Peter’s chief disciple and secretary and was taken to Antioch to assist Paul. He became an exponent of the deeper mysteries of Christianity and founded the Church at Alexandria, where he was later martyred.

Mark is shown on the left serving at the table.

The Biblical account

John was his Jewish name; Mark, or Marcus, was his Roman name, in keeping with the custom of Hellenistic Jews of this time. John means “God is gracious,” i.e., “Upon this place, upon this servant, the grace or the light of Yahweh descends”; Marcus is from the Latin, “a large hammer.”

E. P. Blair writes of Mark’s background:

When we first meet John Mark, he is living at Jerusalem, apparently in the home of his mother, Mary.[2] She appears to have been a widow of some means, inasmuch as she is described in Acts as the owner of a house spacious enough to accommodate a large Christian gathering and as having the services of a maid. It has been suggested that the Last Supper was held in her home and that John as a boy may have witnessed some of the final events of Jesus’ life.

It is further conjectured that the young man who fled away naked in the Garden of Gethsemane[3] was John Mark.[4]

When the guard attempted to arrest him, he ran off leaving only his garment, a linen cloth, in the soldier’s hands.

In the Acts of the Apostles

Mary seems to have been intimately acquainted with Saint Peter, as it was to her house that he repaired after his deliverance from prison.[5] This fact could account for Mark’s intimate acquaintance with Peter. In Peter’s first epistle, Mark is referred to as Peter’s “son”[6]—evidence of close attachment between Peter and Mark.

The Acts of the Apostles records that John Mark was taken by Barnabas and Paul on their first missionary journey as an assistant.[7] Barnabas and Paul arrived at Jerusalem to bring alms from the Christians in Antioch to the Christians in Judea during the famine of A.D. 45. They needed an assistant, and it is likely that it was Barnabas who chose his young cousin or nephew Mark.[8]

We read of the occasion when Paul is represented as instructing Timothy to bring him Mark “for he is very useful in serving me.”[9] John Mark acted as a teacher as well as a travel secretary. At Perga in Pamphylia, when they were about to enter upon the more arduous part of their mission, Mark left the apostles, and for some unexplained reason, returned to Jerusalem—to his mother and his home.[10]

In A.D. 51, Barnabas and Paul resolved to set out on a second missionary journey. On this occasion, Paul resolutely declined to associate himself again with one who “departed from them from Pamphylia, and went not with them to the work.” The issue was a “sharp contention” which resulted in the separation of Paul from his old friend Barnabas who, taking Mark with him, returned to Cyprus while Paul proceeded through Syria and Cilicia.[11]

Whatever the cause of Mark’s apparent vacillation, it did not lead to a final separation between him and Paul. Less than ten years later, Mark shared Paul’s imprisonment in Rome, A.D. 61–63, and he is acknowledged by Paul as one of his few “fellowlabourers unto the kingdom of God” who had been a comfort to him during his imprisonment.[12]

Later life

Ecclesiastical tradition affirms that Saint Mark visited Egypt, founded the church at Alexandria, and became its first bishop.[13]

Butler’s Lives of the Saints records:

The heathens [in Alexandria] called him a magician, on account of his miracles, and resolved upon his death.... At last, on the pagan feast of the idol Serapis, some that were employed to discover the holy man found him offering to God the prayer of the oblation, or the mass. Overjoyed to find him in their power, they seized him, tied his feet with cords, and dragged him about the streets, crying out, that the ox must be led to Bucoles, a place near the sea, full of rocks and precipices, where probably oxen were fed. This happened on Sunday, the twenty-fourth of April, 68, of Nero, the fourteenth, about three years after the death of SS Peter and Paul.

The saint was thus dragged the whole day, staining the stones with his blood, and leaving the ground strewed with pieces of his flesh; all the while he ceased not to praise and thank God for his sufferings. At night he was thrown into prison, in which God comforted him by two visions.... The next day the infidels dragged him, as before, till he happily expired on the twenty-fifth of April. The Christians gathered up the remains of his mangled body, and buried them at Bucoles, where they afterward usually assembled for prayer.[14]

As we remember the lion of Saint Mark and as we study his book, let us learn to thank God and praise him for sufferings less than these. Let us pray that we will be able to bear all things in the true spirit of Christ, as the saints and the martyrs have always done. We need to praise and thank God for his testings of our soul immediately—right when they happen. It needs to be a habit. And it’s a habit of Leo, the lion, God-gratitude of the heart, gratefulness that we are tried and strengthened.

God has to strengthen us. He cannot leave us in a state where everything is done for us, everything works out perfectly. We’ll be flabby, we don’t have any muscles, we won’t have any drive to figure out solutions to the challenges of life. God has to leave us in difficult situations so we can be strengthened, so when he wants to give us a mantle from Sirius or from Morya, he knows that we will have the inner strength to be the coordinate for that mantle.

The Gospel of Mark

Scofield comments on the Gospel of Mark:

Everywhere the servant character of the incarnate Son is manifest. The key verse is Mark 10:45: “For even the Son of man came not to be ministered unto, but to minister.” The characteristic word of this gospel is “straightway,” a servant’s word. There is no genealogy, for who gives the genealogy of a servant?[15]

Whereas Matthew and Luke both include a genealogy, Mark does not consider that the human lineage and descent of Jesus Christ is important. He is not trying to prove that Jesus is Almighty God incarnate, and if he is trying to prove it, he has sense enough to know that you don’t prove it by human genealogy. The Book of Mark, contrasting the Book of Matthew, begins with the going before the face of Jesus of John the Baptist, then the baptism of Jesus. And before you are through the first chapter, you are with Jesus in the wilderness being tempted of the Devil. Mark begins with the mission. He leaves to others to account for his birth in Bethlehem and his early years.

The earliest statement about the Gospel that is in existence concerning Mark comes from Papias around 140 A.D:

Mark, who became Peter’s interpreter, wrote accurately, though not in order, all that he remembered of the things said and done by the Lord. For he had neither heard the Lord nor been one of his followers, but afterward, as I said, he had followed Peter, who used to compose his discourses with a view to the needs [of his hearers], but not as if he were composing a systematic account of the Lord’s sayings. So Mark did nothing blameworthy in thus writing some things just as he remembered them; for he was careful of this one thing, to omit none of the things he had heard and to state no untruth therein.[16]

The Gospel according to Saint Mark was, for many centuries, thought to be merely an abridgment of Matthew—and so tended to be the least valued and least read. It is now widely recognized as the earliest of the Synoptic Gospels. The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible gives the following arguments in support of this position:

(a) The substance of over ninety per cent of Mark’s verses is contained in Matthew, the substance of over fifty per cent in Luke.

(b) Where the same matter is contained in all three Synoptic gospels, usually more than half Mark’s actual words are to be found either in both Matthew and Luke or in one of them... (c) The order in which the material is arranged in Mark is usually followed by both Matthew and Luke....

(d) Often where Matthew and/or Luke and Mark differ in language, the language of [the other evangelists] is either grammatically or stylistically smoother and more correct than that of Mark.

(e) On other occasions something in Mark which could perplex or offend is either absent from, or appears in a less sharp form in, Matthew or Luke....

The statement that Jesus “began to be greatly distressed and troubled” (Mark 14:33) is softer in Matthew 26:37 ... and omitted altogether in Luke; the picture of the three disciples’ failure to watch with Jesus in Gethsemane is considerably softened by the addition of the words “for sorrow” in Luke 22:45; in Mark 14:71 ... Peter is said to have begun “to invoke a curse on himself and to swear, ‘I do not know this man...,’” but Luke has the much less offensive “Man, I do not know what you are saying” (Luke 22:60)....

(f) In Mark the disciples’ pre-Resurrection mode of addressing Jesus (as “Teacher,” “Rabbi”) is faithfully reflected, whereas Matthew and Luke often represent him as addressed by the title “Lord,” thus reflecting the post-Resurrection usage of the church....

If Mark, then, is the earliest of the gospels, its special importance as our primary source of information about the ministry of Jesus is obvious.[17]

The Secret Gospel of Mark

In 1958, Morton Smith discovered at Mar Saba, a Greek Orthodox monastery in the Judean desert, a fragment of a previously unknown letter of the second-century Church Father Clement of Alexandria, which reveals that Mark wrote a secret Gospel:

Mark, then, during Peter’s stay in Rome ... wrote [an account of] the Lord’s doings, not, however, declaring all [of them], nor yet hinting at the secret [ones], but selecting those he thought most useful for increasing the faith of those who were being instructed. But when Peter died as a martyr, Mark came over to Alexandria, bringing both his own notes and those of Peter, from which he transferred to his former book the things suitable to whatever makes for progress toward knowledge [gnosis]. [Thus] he composed a more spiritual Gospel for the use of those who were being perfected. Nevertheless, he yet did not divulge the things not to be uttered, nor did he write down the hierophantic[18] teaching of the Lord, but to the stories already written he added yet others and, moreover, brought in certain sayings of which he knew the interpretation would, as a mystagogue,[19] lead the hearers into the innermost sanctuary of that truth hidden by seven [veils]. Thus, in sum, he prearranged matters, neither grudgingly nor incautiously, in my opinion, and, dying, he left his composition to the church in Alexandria, where it even yet is most carefully guarded, being read only to those who are being initiated into the great mysteries.[20]

Smith and other scholars analyzed the fragment of Clement’s letter and the majority agreed it had in fact been written by the Church Father. Smith then concluded from stylistic study that secret Mark did not belong to the family of New Testament apocrypha composed during and after the late second century, but that it had been written at least as early as A.D. 100–120.[21] Furthermore, from other clues Smith makes a good case for it having been written even earlier—around the same time as the Gospel of Mark.[22]

The significance of Secret Mark

Most significantly, the fragment reveals more about Jesus’ secret practices. It contains a variant of the Lazarus story, which theretofore was found only in the Book of John.[23] Secret Mark says that after the resurrection of the Lazarus figure (Clement’s fragment leaves him nameless), the youth,

looking upon him [Jesus], loved him, and began to beseech him that he might be with him. And going out of the tomb they came into the house of the youth, for he was rich. And after six days Jesus told him what to do and in the evening the youth comes to him, wearing a linen cloth over [his] naked [body]. And he remained with him that night, for Jesus taught him the mystery of the kingdom of God.[24]

This story, coupled with the very existence of a secret Gospel, strengthens the evidence for secret teachings and initiatic rites. Clement’s reference to Mark having combined his notes with “those of Peter” supports the theory that the immediate followers of Jesus were literate and kept a record of their Lord’s teachings—if not a historical diary.

Secret Mark casts the official canon in another light. Could the Gospels themselves be the “exoteric” teachings, for those who were “without,” so intended by their authors from the start? Clement tells us that Mark’s secret Gospel was for those “who were being perfected,” i.e., in the language of Paul—“we speak wisdom among them that are perfect”—initiated.

Jesus’ secret teachings

The Lazarus story appears in the New Testament only in the Book of John. It had always seemed strange that only one of the Gospels should record this most important miracle by Jesus—the raising of the dead. This fragment from Secret Mark not only provides reinforcement for the Lazarus miracle but also explains a portion of the Gospel of Mark which has baffled scholars for centuries.

At the point of Jesus’ arrest on the Mount of Olives, Mark gives the following verses:

And there followed him a certain young man, having a linen cloth cast about his naked body; and the young men laid hold on him:

And he left the linen cloth, and fled from them naked.[25]

Smith reasons that Jesus was baptizing the young man in a rite similar to that which he administered to the Lazarus figure in the secret gospel after he had raised him from the dead. The circumstances are the same, he says—similar attire, nocturnal meeting—and the stream at the foot of the Mount of Olives could have provided the water.[26] This seems the best explanation yet for the presence of the peculiarly attired young man at Jesus’ arrest.

See also

Sources

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, June 17, 1981.

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Masters and Their Retreats, s.v. “Lanello.”

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, Lost Teachings of Jesus: Missing Texts • Karma and Reincarnation, pp. xlvii–xlix.

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, Lost Teachings on Keys to Spiritual Progress, pp. 19–21.

- ↑ Ezek. 1:10.

- ↑ Acts 12:12, 25.

- ↑ Mark 14:51–52.

- ↑ The Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible (Nashville, New York: Abingdon Press, 1962), s.v. “Mark, John,” 3:277.

- ↑ Acts 12:12.

- ↑ 1 Pet. 5:13.

- ↑ Acts 13:5.

- ↑ Acts 12:25; Col. 4:10.

- ↑ 2 Tim. 4:11.

- ↑ Acts 13:13.

- ↑ Acts 15:36–39.

- ↑ Col. 4:10–11; Phil. 24.

- ↑ One reason for Mark coming to Egypt was his earlier embodiment there as Ikhnaton.

- ↑ Alban Butler, Lives of the Saints (Burns and Oates, 1899), 4:317.

- ↑ The Scofield Reference Bible (New York: Oxford university Press, 1945), p. 1045.

- ↑ Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, s.v. “Mark, Gospel of,” 3:267.

- ↑ Interpreter’s Dictionary of the Bible, s.v. “Mark, Gospel of,” 3:269, 271.

- ↑ Hierophantic [from Greek hieros, powerful, supernatural, holy, sacred + phantes, from phainein, to bring to light, reveal, show, make known]: of, relating to, or resembling a hierophant, who in antiquity was an official expounder of sacred mysteries or religious ceremonies, esp. in ancient Greece.

- ↑ Mystagogue: one who initiates another into a mystery cult

- ↑ Morton Smith, The Secret Gospel: The Discovery and Interpretation of the Secret Gospel According to Mark (Dawn Horse Press, 1982), p. 15. Note: Words in brackets were added in by Smith for clarity.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 40.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 61.

- ↑ John 11:1–44.

- ↑ Smith, The Secret Gospel, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Mark 14:51–52.

- ↑ Smith, The Secret Gospel, p. 15.