Akbar el Grande

Abu’l-Fath Jalal ud-din Muhammad Akbar (1542–1605) is honored as the greatest of the Mogul emperors of India and as a father of religious tolerance. He believed he was a divinely appointed ruler and that it was his mission to unify his empire. According to court historian Abul Fazl, Akbar’s entire life was a search for Truth. He was an embodiment of the Ascended Master El Morya.

Vida temprana

Akbar nació en 1542 en Umarkot. Cuando Akbar Jalal Ud-bin Mohammed heredó el trono en 1556, el imperio mogol en la India del siglo dieciséis había sido reducido por aguerridas conquistas extranjeras al grado de que casi solamente la capital, Nueva Delhi, permanecía en efecto.

Not yet fourteen at his accession, the brilliant young Emperor Akbar set out to reconquer his realm. He became known throughout the world as Akbar the Great—the most powerful of the Mogul emperors. Tremendous physical stamina characterized Emperor Akbar and contributed to his extraordinary military success—he could ride 240 miles in twenty-four hours to surprise and defeat the enemy. Nevertheless, it took the major part of his long reign (1556–1605) to subject the rebellious princes of northern India and to secure peace by establishing sound provincial governments.

Akbar estaba dotado de ingenio para la administración. Incrementó la efi cacia del comercio construyendo caminos, desarrollando avanzados sistemas de mercado e instituyendo servicios postales. Legítimamente preocupado por todos los pueblos que estaban bajo su jurisdicción, Akbar abolió la detestada jizya, el impuesto que se recaudaba entre los no musulmanes, y dio a los hindúes posiciones prominentes en el gobierno. La nueva ciudad capital, Fatehpur Sikri, pronto se convirtió en un centro cultural fl oreciente, más grande que la ciudad de Londres a la sazón.

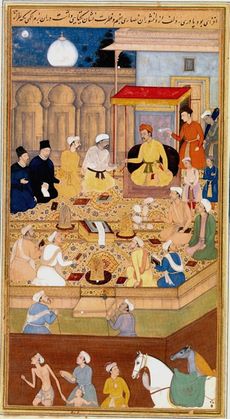

Akbar favoreció grandemente el arte indio; bajo su dirección se establecieron más de cien talleres para las artes manuales. El emperador amaba la música y la fomentaba como medio de comunicación entre hindúes y musulmanes. Aunque era analfabeta, la biblioteca de manuscritos ilustrados de Akbar era tan célebre como las más finas colecciones de Europa.

By the end of his fifty-year rule in 1605, the small territory he had inherited was an empire that extended from the Hindu Kush to the Godavari River and from Bengal to Gujarat (present-day Bangladesh and most of Nepal, India, Pakistan and Afghanistan). Through Akbar’s military genius and vigorous leadership, the Mogul empire became one of the most powerful in the world. He implemented numerous administrative reforms that strengthened the governmental structure, abolished extortion, and centralized the financial system. Although he could neither read nor write, Akbar ably conversed with scholars and religious men and sponsored a renaissance in art and literature.

Religious tolerance

The emperor was born a Muslim but respected Hindu religion and culture and offered Hindus and Muslims alike the highest posts in his government. He assembled scholars of the Muslim and Hindu sects, Jains, Zoroastrians, and Jesuits in his capital, where in 1575 he built an ibadat khana, a “house of worship,” where learned men of all religions could meet to discuss both theology and philosophy. In an attempt to resolve the discord among the many religious factions in his empire, and recognizing the limitations of each, he proposed that “we ought, therefore, to bring them all into one, but in such fashion that they should be both ‘one’ and ‘all’, with the great advantage of not losing what is good in any one religion, while gaining whatever is better in another.” The members of the council could not agree among themselves, however, and remained supportive only of their own religions.

In 1582 Akbar founded his own religion, Din-i-Ilahi, “divine faith,” or Tauhid-i-Ilahi, “divine monotheism,” with himself as its spiritual leader. As Abul Fazl comments, Akbar, in establishing the tenets of the new religion, “seized upon whatever was good in any religion.... He is truly a man who makes Justice his leader in the path of inquiry, and who culls from every sect whatever Reason approves of.” Akbar did not, however, demand that his countrymen espouse his beliefs, and Akbar’s new religion had few adherents outside his court.

Final years

Al final de su reinado, la paz y la prosperidad que Akbar había traído a la India fueron perturbadas por intrigas en la corte y las actividades subversivas de su hijo, Jahangir. Cuando éste heredó el trono, rechazó las reformas de su padre, especialmente la de la tolerancia religiosa, y el imperio rápidamente se desmoronó. El hijo de Jahangir, el Shah Jahan, heredó tan sólo un pequeño reino desorganizado e indisciplinado, pero tenía un gran amor por el legado cultural de su abuelo. El más grande de los arquitectos mogoles, el cha Jahan dio a la India su tesoro más preciado: el Taj Mahal.

The universal religion

In 1985 El Morya spoke of his embodiment as Akbar and his dream of a universal religion:

Beloved sons and daughters, I remember well and I would remind you of my incarnation as Akbar. So Islam, the religion of my birth—Hinduism, the religion of my nation. So, juxtaposed midst all of this, I did perceive that all religions were found wanting. Therefore I assembled the representatives of all faiths and sects within the larger religions, that they might deliberate, that they might also convince me of their way. I had purposed in my heart to lead each group to the point of the realization of the quintessence of the Light of the Child whom I had seen at his birth hundreds of years before.

Thus, the memory of the Christ Child impelled me to draw others to the divine resolution of the Light and to the dissolution of the barriers to the free expression of that Light. And so it came to pass that I did point out to each group the limitations that made each version of religion incomplete. And I did propose to take the best from all and leave the rest and arrive at that doctrine upon which all could agree as the basis of the new world religion. But they objected and objected vehemently. And therefore I was left with a band of disciples, a circle of followers of my own court, who recognized God as Light and saw me not only as their secular leader but as their spiritual head.

Thus, you see, I came into the office of Guru through the acceptance and love of those who respected the power and the will of God they saw within me and my devotion to the integrity and the honor of that will. Thus, all religions were free to practice in the realm and any were free to be a part of my circle.

I bring this to your attention because as you read the life of Akbar, you may find yourself in my family and circle of the court, certainly harking back to the court of Camelot[1] and the chelas of the will of God who have been with me for so many centuries.[2]

See also

El Morya, “The Universal Religion,” Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 28, no. 51, December 22, 1985.

For more information

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, Lords of the Seven Rays.

Lecture by Elizabeth Clare Prophet, “Akbar the Great: The Shadow of God on Earth,” August 8, 1993. Available from Ascended Master Library.

Sources

El Morya, “The Universal Religion,” Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 28, no. 51, December 22, 1985.

El Morya’s Christmas Letter 1994

- ↑ El Morya was embodied as King Arthur.

- ↑ El Morya, “The Universal Religion,” Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 28, no. 51, December 22, 1985.