Zaratustra

Atualmente, este cargo da Hierarquia é ocupado por aquele que encarnou na Pérsia antiga como fundador do Zoroastrismo. Ele é o mais alto iniciado do fogo sagrado do planeta e a autoridade responsável pelas energias do fohat. Zaratustra coordena os sacerdotes do fogo sagrado e o sacerdócio de Melquisedeque.

Todos os membros da Grande Fraternidade Branca servem na Ordem de Melquisedeque, assim como servem o fogo sagrado, mas somente os que alcançaram um certo nível de iniciação podem ser chamados Sacerdotes da Ordem de Melquisedeque. Os outros membros servem os propósitos da Ordem, mas não recebem o título de sacerdotes. Zaratustra tem muitos discípulos que servem sob a sua direção, e quando o mais avançado alcança uma certa mestria, é considerado apto para o cargo, e o professor pode passar para o serviço cósmico.

O registro histórico

O Zoroastrismo é uma das religiões mais antigas do mundo. Zaratustra, o seu fundador, foi um profeta que conversava diretamente com Deus.

Mary Boyce, Professora Emérita de Estudos Iranianos da Universidade de Londres, salienta:

Zoroastrismo é a mais antiga das religiões mundiais reveladas e, provavelmente, teve mais influência na humanidade, direta e indiretamente, do que qualquer outra fé.[1]

De acordo com R. C. Zaehner, ex-Professor Spalding de Religiões Orientais e Ética na Universidade de Oxford, Zaratustra foi

... one of the greatest religious geniuses of all time.... [He] was a prophet, or at least conceived himself to be such; he spoke to his God face to face.... [Yet] about the Prophet himself we know almost nothing that is authentic.[2]

Zaratustra viveu em uma sociedade inculta, que nada registrava. Os seus ensinamentos foram transmitidos oralmente e muito do que foi escrito mais tarde sobre a sua vida e os seus ensinamentos perdeu-se ou foi destruído. O material que os estudiosos conseguiram reunir sobre o Iniciado proveio de três fontes: o estudo do meio social, antes da época e na época em que se acredita que ele tenha vivido; a tradição e os Gathas, dezessete hinos sagrados supostamente compostos por ele. Os Gathas estão registrados no Avesta, as escrituras sagradas do Zoroastrismo.

Acredita-se que Zaratustra tenha nascido na região leste do Irã atual, mas não há uma certeza sobre isso. A sua data de nascimento ainda é mais difícil de estabelecer. Os eruditos calculam que seja algo entre 1700 a.C. e 600 a.C., mas o consenso geral é de que ele tenha vivido por volta de 1000 a.C..

The Gathas are the key to determining Zarathustra’s approximate year of birth. They are linguistically similar to the Rigveda, one of the sacred texts of the Hindus. According to Boyce:

The language of the Gathas is archaic, and close to that of the Rigveda (whose composition has been assigned to about 1700 B.C. onwards); and the picture of the world to be gained from [the Gathas] is correspondingly ancient, that of a Stone Age society.... It is only possible therefore to hazard a reasoned conjecture that [Zarathustra] lived some time between 1700 and 1500 B.C.[3]

Other scholars working with the same evidence place his birth between 1400 and 1200 B.C.

The Gathas say that Zarathustra was of the Spitama family, a family of knights. The Greek name for Zarathustra is Zoroaster, meaning “Golden Star,” or “Golden Light.” He was one of the priest class who formulated mantras.

Zarathustra was also an initiate. According to Boyce, “He ... describes himself [in the Gathas] as a ‘vaedemna’ or ‘one who knows,’ an initiate possessed of divinely inspired wisdom.”[4] But first and foremost, Zarathustra was a prophet, and he is a prophet and he lives today among us as an ascended master.

The Gathas depict him as talking to God. They say:

He is “the Prophet who raises his voice in veneration, the friend of Truth,” God’s friend, a “true enemy to the followers of the Lie and a powerful support to the followers of the Truth.”[5]

Calling as a prophet

Segundo a tradição, aos vinte anos, Zaratustra deixou pai, mãe e esposa para ir em busca da Verdade. Dez anos mais tarde, teve a primeira de muitas visões.

Boyce writes:

According to tradition Zoroaster was thirty, the time of ripe wisdom, when revelation finally came to him. This great happening is alluded to in one of the Gathas and is tersely described in a Pahlavi [Middle Persian] work. Here it is said that Zoroaster, being at a gathering [called] to celebrate a spring festival, went at dawn to a river to fetch water.

He waded in to draw [the water] from midstream; and when he returned to the bank ... he had a vision. He saw on the bank a shining Being, who revealed himself as Vohu Manah ‘Good [Mind]’; and this Being led Zoroaster into the presence of Ahura Mazda and five other radiant figures, before whom ‘he did not see his own shadow upon the earth, owing to their great light’. And it was then, from this great heptad [or group of seven beings], that he received his revelation.”[6]

We can conjecture that the seven beings of this great heptad were none other than the Seven Holy Kumaras.

Ahura Mazda significa “Senhor Sábio” e Zaratustra reconheceu em Ahura Mazda o Deus Verdadeiro, o Criador do universo.

The significance of this cannot be overstated. Zarathustra may have been the first monotheist in recorded history. Zaehner points out, “The great achievement of the Iranian Prophet [was] that he eliminated all the ancient gods of the Iranian pantheon, leaving only Ahura Mazdah, the ‘Wise Lord’, as the One True God.”[7]

Some scholars assert that Zarathustra was not a strict monotheist but a henotheist, that is, one who worships one God but does not deny the existence of others. This is a technical distinction. As David Bradley, author of A Guide to the World’s Religions, notes, “[Zarathustra] was a practicing monotheist in the same way that Moses was.”[8] Bradley thinks that Moses knew of the existence of lesser gods but insisted on the necessity of siding with the true God against all other gods.[9]

Shortly after his first vision, Zarathustra became a spokesman for Ahura Mazda and began to proclaim his message.

According to Simmons, Zarathustra instituted a religious reform that was more far-reaching and more radical than Martin Luther’s challenge of the Roman Catholic Church.[10]

Zarathustra’s reform had a number of facets. His main objective was to stamp out Evil. He began to condemn the religious doctrines of his countrymen.

The old religion, as best we can tell, had two classes of deities—the ahuras, or “lords,” and the daevas, or “demons.” According to Zaehner:

It is ... the daevas specifically whom Zoroaster attacks, not the ahuras whom he prefers to ignore.... In all probability he considered them to be God’s creatures and as fighters on his side. In any case he concentrated the full weight of his attack on the daevas and their worshippers who practised a gory sacrificial ritual and were the enemies of the settled pastoral community to which the Prophet himself belonged.[11]

Spreading his message

No início da sua missão, Zaratustra não teve sucesso. Zaehner observa: “É óbvio a partir dos Gathas que Zoroastro encontrou forte oposição das autoridades civis e eclesiásticas quando, uma vez, proclamou sua missão.” [12] Os sacerdotes e os seguidores dos “daevas” perseguiam-no e, segundo a tradição, tentaram matá-lo inúmeras vezes.

Somente após uma década Zaratustra conseguiu a primeira conversão: a de um primo seu. Depois, foi conduzido divinamente, até à corte do Rei Vishtaspa e da Rainha Hutaosa.

Vishtaspa, era um monarca honesto e simples, mas vivia rodeado de karpans, um grupo de sacerdotes manipuladores que só se preocupavam com eles mesmos. Eles convocaram um conselho para confrontar as revelações do novo profeta, e conseguiram mandá-lo para a prisão. De acordo com a história, Zaratustra ganhou a liberdade quando, por milagre, curou um cavalo negro, o favorito do rei. Vishtaspa deu-lhe permissão para ensinar a nova fé à sua consorte, a rainha Hutaosa. A bela Hutaosa tornou-se uma das principais protetoras de Zaratustra e ajudou-o a converter Vishtaspa.

Após dois longos anos, o monarca converteu-se, mas exigiu um último sinal, antes de aderir totalmente à fé. Ele pediu que lhe fosse mostrado o papel que teria no mundo celestial. Por isso, Ahura Mazda enviou três arcanjos para a corte de Vishtaspa e Hutaosa. Os três pareciam cavaleiros resplandecentes, usavam armaduras e montavam cavalos. De acordo com um texto, eles chegaram com tamanha glória, que a radiação “dos três naquela moradia eminente assemelhava-se a...um céu pleno de luz, devido ao seu imenso poder e triunfo. Quando olhou para os arcanjos, o nobre rei Vishtaspa e os cortesãos estremeceram, e os comandantes ficaram confusos”.[13]

Irradiando uma luz ofuscante e o som do ribombar do trovão, os arcanjos anunciaram que vinham em nome de Ahura Mazda e traziam uma mensagem de Zaratustra. Eles prometeram a Vishtaspa que ele viveria cento e cinquenta anos, e que ele e Hutaosa teriam um filho imortal. No entanto, os arcanjos avisaram que, caso ele não aceitasse a religião, seu fim estaria próximo. O rei abraçou a fé e foi seguido por toda a corte. As escrituras registram que os arcanjos passaram a viver com Vishtaspa.

Mensageiro de Sanat Kumara

Em um ditado transmitido em 1° de janeiro de 1981, o Mestre Ascenso Zaratustra referiu-se ao rei Vishtaspa e à rainha Hutaosa:

Venho para conceder o fogo sagrado do Sol por detrás do sol, que vos elevará e estabelecerá em vós o ensinamento original de Ahura Mazda, Sanat Kumara, transmitido há muito tempo, na antiga Pérsia, a mim, ao rei e à rainha que foram convertidos pelos arcanjos, pelo fogo sagrado e pelos santos anjos, por meio da descida da luz. Como as suas correntes de vida aceitaram a minha profecia, multiplicou-se o pão da vida do coração de Sanat Kumara, do qual fui mensageiro, e continuo sendo.

Os ensinamentos das hostes do SENHOR e a vinda do grande avatar de luz, os ensinamentos sobre a traição e a subsequente guerra da suas hostes contra os malvados, foram compreendidos e propagados. A lei do carma, a lei da reencarnação e mesmo a visão dos últimos dias, quando o mal e o Ser Maligno seriam derrotados – tudo isso contribuiu para a conversão do Rei e da Rainha e para a propagação da fé entre todos os súbditos do país. Por intermédio do meu cargo, os arcanjos puseram à prova os dois eleitos. Ao serem aprovados, foram abençoados como emissários secundários de Sanat Kumara. E, portanto, eu, o profeta, e eles mantendo o equilíbrio na Terra, manifestamos uma trindade de luz e o fluxo da figura em forma de oito.

Identificai os ingredientes necessários à propagação da fé por todo o planeta. Os arcanjos enviaram o seu mensageiro com uma dádiva de profecia, que é a Palavra de Sanat Kumara para todas as culturas e para todas as eras. O profeta vem com a visão, a unção e o fogo sagrado. Mas, a menos que o profeta encontre um campo fértil de corações chamejantes e receptivos, a autoridade da Palavra não será transmitida ao povo.[14]

Ahura Mazda

Zarathustra recognized Ahura Mazda, the Wise Lord, as the creator of all, but he did not see him as a solitary figure. In Zoroastrianism, Ahura Mazda is the father of Spenta Mainyu, the Holy Spirit. Spenta means “holy” or “bountiful.” Mainyu means “spirit” or “mentality.” The Holy Spirit is one with, yet distinct from, Ahura Mazda. Ahura Mazda expresses his will through Spenta Mainyu.

Boyce explains:

For Zarathushtra God was Ahura Mazda, who ... had created the world and all that is good in it through his Holy Spirit, Spenta Mainyu, who is both his active agent and yet one with him, indivisible and yet distinct.[15]

Simply put, the Spirit is always the Spirit of the Lord. When we speak of the Holy Spirit, it is the Spirit of God.

Ahura Mazda is also the father of the Amesha Spentas, or six “Holy” or “Bountiful Immortals.” Boyce says that the term spenta is one of the most important in Zarathustra’s theology. To him, it meant “possessing power.” When used in connection with the beneficent deities, it meant “possessing power to aid” and hence “furthering, supporting, benefiting.”[16]

Zarathustra taught that Ahura Mazda created the world in seven stages. He did so with the help of the six great Holy Immortals and his Holy Spirit. The term Amesha Spenta can refer to any one of the divinities created by Ahura Mazda but refers especially to the six who helped create the world. According to Boyce:

These divinities formed a heptad with Ahura Mazda himself.... Ahura Mazda is said either to be their “father”, or to have “mingled” himself with them, and in one ... text his creation of them is compared with the lighting of torches from a torch.

The six great Beings then in their turn, Zoroaster taught, evoked other beneficent divinities, who are in fact the beneficent gods of the pagan Iranian pantheon.... All these divine beings, who are...either directly or indirectly the emanations of Ahura Mazda, strive under him, according to their various appointed tasks, to further good and to defeat evil.[17]

The six Holy or Bountiful Immortals also represent attributes of Ahura Mazda. The Holy Immortals are as follows:

Vohu Manah, whose name means “Good Mind,” “Good Thought” or “Good Purpose.” According to Boyce, “For every individual, as for the prophet himself,” Vohu Manah is “the Immortal who leads the way to all the rest.” Asha Vahishta, whose name means “Best Righteousness,” “Truth” or “Order,” is the closest confederate of Vohu Manah.[18]

Spenta Armaiti, “Right-mindedness” or “Holy Devotion,” Boyce says, embodies the dedication to what is good and just. Khshathra Vairya, “Desirable Dominion,” represents the power that each person should exert for righteousness as well as the power and the kingdom of God.[19]

The final two are a pair. They are Haurvatat, whose name means “Wholeness” or “Health,” and Ameretat, whose name means “Long Life” or “Immortality.” Boyce says these two enhance earthly existence and confer eternal well-being and life, which may be obtained by the righteous in the presence of Ahura Mazda.[20] She says:

The doctrine of the Heptad is at the heart of Zoroastrian theology. Together with [the concept of Good and Evil] it provides the basis for Zoroastrian spirituality and ethics, and shapes the characteristic Zoroastrian attitude of responsible stewardship for this world.[21]

In later tradition, the six Holy Immortals were considered to be Archangels.

The nature of good and evil

When it came to Good and Evil, Zarathustra tended to see things in terms of black and white. According to Zaehner:

The Prophet knew no spirit of compromise.... On the one hand stood Asha—Truth and Righteousness—[and] on the other the Druj—the Lie, Wickedness, and Disorder. This was not a matter on which compromise was possible [as far as Zarathustra was concerned].... The Prophet [forbade] his followers to have any contact with the “followers of the Lie.”[22]

The origin of the conflict between Truth and the Lie is described in the Gathas. It is presented as a myth about two Spirits, called twins, who must make a choice between Good and Evil at the beginning of time. One of the two is the Holy Spirit, the son of Ahura Mazda. The other is the Evil Mind or the Evil Spirit, Angra Mainyu.

Zarathustra introduced the myth with the following words, which underscore the all-important concept of free will and that every man must choose the Truth or the Lie: “Hear with your ears, behold with mind all clear the two choices between which you must decide, each man [deciding] for his own self, [each man] knowing how it will appear to us at the [time of] great crisis.”[23] Then he proceeded to recount the myth:

In the beginning those two Spirits who are the well-endowed twins were known as the one good and the other evil, in thought, word, and deed. Between them the wise chose rightly, not so the fools. And when these Spirits met they established in the beginning life and death that in the end the followers of the Lie should meet with the worst existence, but the followers of Truth with the Best Mind.

Of these two Spirits he who was of the Lie chose to do the worst things; but the Most Holy Spirit, clothed in rugged heaven, [chose] Truth as did [all] who sought with zeal to do the pleasure of the Wise Lord by [doing] good works.

Between the two the daevas [the demons] did not choose rightly; for, as they deliberated, delusion overcame them so that they chose the most Evil Mind. Then did they, with one accord, rush headlong unto Fury that they might thereby extinguish the existence of mortal men.[24]

The Holy Spirit and the Evil Spirit are, as Zaehner puts it, “irreconcilably opposed to each other.”[25] Zarathustra said:

I will speak out concerning the two Spirits of whom, at the beginning of existence, the Holier thus spoke to him who is Evil: “Neither our thoughts, nor our teachings, nor our wills, nor our choices, nor our words, nor our deeds, nor our consciences, nor yet our souls agree.”[26]

Zaehner notes that this state of conflict affected every sphere of activity human or divine. In the social sphere, the conflict took place between the pastoral communities of peaceful cattle breeders, who were “followers of Truth or Righteousness,” and the bands of predatory nomads, who raided the cattle breeders. Zarathustra called these predatory nomads the “followers of the Lie.”[27]

On the religious plane, the conflict took place between Zarathustra and his followers and those who were followers of the traditional Iranian religion and worshiped the daevas. The adherents of this ancient religion said it was founded by Yima, the child of the Sun. Zarathustra attacked Yima and the ritual of animal sacrifice he had introduced.[28]

He also condemned the rite associated with drinking haoma, the fermented juice of a plant that caused “filthy drunkenness.”[29] Scholars are not sure what haoma was, but they conclude from the description of the effects it had on those who drank it that it probably contained a hallucinogen. Zaehner writes: “For Zoroaster the whole cult with its bloody sacrifice and ritual drunkenness is anathema—a rite offered to false gods and therefore a ‘lie’.”[30]

Zarathustra said “the followers of the Lie” destroyed life and strove to “sever the followers of Truth from the Good Mind.”[31] The followers of the Lie knew who Zarathustra was, recognized the danger he represented and did everything they could to destroy him. To this end, they continued to sacrifice bulls and participate in the haoma rite. According to Zaehner:

There would seem to be little doubt that an actual state of war existed between the two parties, Zoroaster and his patron Vishtaspa standing on the one side and the so-called followers of the Lie, many of whom he mentions by name, on the other.[32]

Finally, the battle went on right within man. John Noss, author of Man’s Religions, observes that “it was perhaps Zoroaster’s cardinal moral principle, that each man's soul is the seat of a war between good and evil.”[33]

One of the principal weapons used to attack demons and evil men was the prayer written by Zarathustra, the Ahuna Vairya. This short prayer is the most sacred of Zoroastrian prayers:

As the Master, so is the Judge to be chosen in accord with Truth. Establish the power of acts arising from a life lived with good purpose, for Mazda and for the lord whom they made pastor for the poor.[34]

The lord in the last line of this prayer is thought to be Zarathustra himself. The prayer is ancient. It is written in the style of the Rigveda. According to Simmons, this prayer is a mantra. Simmons says that Zoroastrians believe that “pronouncing words in Zoroastrian ritual has an effect on the external world.” They believe that if a particular mantra is pronounced correctly, it will affect outer circumstances.[35]

Zaehner sums up:

For Zoroaster there is only one God, Creator of heaven and earth and of all things. In his relations with the world God acts through his main “faculties” which are sometimes spoken of as being engendered by him—his Holy Spirit, [his] Righteousness, [his] Good Mind, and Right-mindedness. Further he is master of the Kingdom, Wholeness, and Immortality, which also form aspects of himself.

Righteousness or Truth is the objective standard of right behaviour which God chooses.... Wickedness or disorder ... is the objective standard of all that strives against God, the standard which the Evil Spirit chooses at the beginning of existence. Evil imitates the good creation: and so we find the Evil Spirit operating against the Holy Spirit, the Evil Mind against the Good Mind, the Lie or wickedness against Truth or Righteousness, and Pride against Right-mindedness.

Evil derives from the wrong choice of a free being who must in some sense derive from God, but for whose wickedness God cannot be held responsible. Angra Mainyu or Ahriman, [names for] the Devil, is not yet co-eternal with God as he was to become in the later system: he is the Adversary of the Holy Spirit only, not of God himself.[36]

But in the end, according to Zoroastrian doctrine, Good will triumph over Evil. These concepts about the birth of Evil very closely parallel the concept of the birth of Evil found in the Kabbalah.

Morality

Zarathustra’s concept of morality can be summed up with the words “good thoughts, good words, good deeds.”[37] This is the threefold ethic of Zoroastrianism. Boyce writes:

All Zoroastrians, men and women alike, wear [a] cord as a girdle, passed three times round the waist and knotted at back and front. Initiation took place at the age of fifteen; and thereafter, every day for the rest of his life, the believer must himself untie and retie the cord repeatedly when praying. The symbolism of the girdle (called in Persian the “kusti”) was elaborated down the centuries; but it is likely that from the beginning the three coils were intended to symbolize the threefold ethic of Zoroastrianism, and so to concentrate the wearer's thoughts on the practice of his faith.

Further, the kusti is tied over an inner shirt of pure white, the “sudra,” which has a little purse sewn into the throat; and this is to remind the believer that he should be continually filling its emptiness with the merit of good thoughts, words and deeds, and so be laying up treasure for himself in heaven.[38]

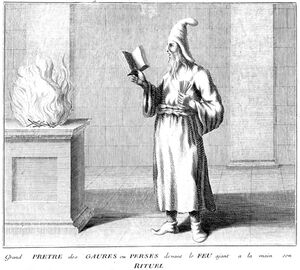

Fire in Zoroastrianism

Fire also plays a central role in Zarathustra’s religion. Fire was a symbol of Ahura Mazda. It was also a symbol of Truth because of its power to destroy darkness.[39] Bernard Springett writes in his book Zoroaster, the Great Teacher:

Fire, the great object of reverence of Zoroaster’s disciples,... has ever been looked upon as a symbol of Spirit, and of Deity, representing the ever-living and ever-active light—essence of the Supreme Being. The perpetual preservation of fire is the first of the five things consecrated by Zoroaster.... The perpetual preservation of fire typifies the essential truth that every man should in like manner make it his constant object to preserve the divine principle in himself which it symbolises.[40]

Legado

Segundo a tradição, Zaratustra foi assassinado por um sacerdote da antiga religião iraniana, quando tinha setenta e sete anos de idade. Springett escreve que “relatos fabulosos da morte de Zoroastro são dados pelos escritores patrísticos gregos e latinos, que afirmam que ele pereceu por um raio ou uma chama do céu.”[41]

Muito do que se passou após a morte do profeta está cercado de mistérios. Os eruditos dizem que os seus sucessores reintroduziram no sistema os antigos deuses que ele destronara.

No século sete a.C., época em que os medas assumiram o poder, o Zoroastrismo era a principal força na Pérsia. Em 331 a.C., quando conquistou aquele país, Alexandre, o Grande, matou os sacerdotes e queimou o palácio real, destruindo todos os registros da tradição zoroastrista.

As Boyce describes it:

The Zoroastrians sustained irreparable loss through the death of so many of their priests. In those days, when all religious works were handed down orally, the priests were the living books of the faith, and with mass slaughters many ancient works (the tradition holds) were lost, or only haltingly preserved.[42]

Por volta do ano 225, o Zoroastrismo ressurgiu na Pérsia e ali se manteve, como religião oficial, até 651, quando os muçulmanos conquistaram o país. Embora a religião fosse tolerada, os conquistadores árabes incentivavam a conversão dos fiéis ao islamismo pressionando-os socialmente, dando incentivos econômicos ou pela força. Muitos zoroastristas se converteram ou optaram pelo exílio. Os zoroastristas leais que permaneceram na Pérsia tiveram de pagar impostos pelo privilégio de praticar a sua fé. Séculos mais tarde a perseguição aos zoroastristas aumentou. Em 1976, havia apenas cento e vinte e nove mil deles no mundo. Muito do que Zaratustra ensinou permanece vivo no Judaísmo, no Cristianismo e no Islamismo.[43]

According to Zaehner:

Zoroastrianism has practically vanished from the world today, but much of what the Iranian Prophet taught lives on in no less than three great religions—Judaism, Christianity and Islam. It seems fairly certain that the main teachings of Zoroaster were known to the Jews in the Babylonian captivity, and so it was that in those vital but obscure centuries that preceded the coming of Jesus Christ Judaism had absorbed into its bloodstream more of the Iranian Prophet’s teaching than it could well admit.

It seems probable that it was from him and from his immediate followers that the Jews derived the idea of the immortality of the soul, of the resurrection of the body, of a Devil who works not as a servant of God but as his Adversary, and perhaps too of an eschatological Saviour who was to appear at the end of time. All these ideas, in one form or another, have passed into both Christianity and Islam.[44]

The mystical path of Zoroastrianism

Some modern-day Zoroastrians say that Zarathustra taught a path of mystical union with God. Dr. Farhang Mehr, a founder of the World Zoroastrian Organization, says that the Zoroastrian mystic seeks union with God but retains his identity. In his book The Zoroastrian Tradition, he writes: “In uniting with God, man does not vanish as a drop in the ocean.”[45]

Mehr says that Zarathustra was “the greatest mystic” and that the path of mysticism is rooted in the Gathas. According to Mehr, the path of mysticism in Zoroastrianism is called the path of Asha, or the path of Truth or Righteousness.[46]

Mehr delineates six stages in this path, which he correlates to the attributes of the six Holy Immortals. In the first stage the mystic strengthens the good mind and discards the evil mind. In the second stage he embodies righteousness. In the third he acquires divine courage and power. This enables him to selflessly serve his fellowman.

In the fourth stage the mystic acquires universal love. This allows him to replace self-love with a universal love—God’s love for all. In the fifth stage he achieves perfection, which is synonymous with self-realization. And in the sixth and final stage, he achieves immortality, communion (or union) with God.[47]

Seu serviço como mestre ascenso

Zaratustra é hoje um mestre ascenso cuja consciência carrega uma emanação áurica ígnea, que é um amor todo-consumidor, uma luz penetrante que alcança o núcleo de tudo o que é irreal. Nós consideramo-lo um Buda porque ele tem a mestria da expansão da chama trina e da mente Crística até ao nível de iniciação Búdica.

Estar na presença de Zaratustra é como estar na presença do próprio sol físico. A mestria que ele tem de fogo espiritual e físico é, se não a maior, uma das maiores entre os adeptos que ascenderam neste planeta. Se quisermos manter a chama de Zaratustra, devemos visualizá-lo guardando a chama, a centelha divina, no seu próprio coração. Ele é o maior de todos “os guardiães do fogo”. Quando o invocarmos, quando estivermos envolvidos na batalha entre a Luz e as Trevas e fizermos o seu chamado para atar as forças do Anticristo, lembremo-nos que Zaratustra é o principal destruidor das forças das trevas. Ele é um mestre ascenso que atingiu a mestria Búdica, cuja emanação áurica está imbuída de um amor que a tudo consome.

Retiro

► Artígo principal: Retiro de Zaratustra

O retiro de Zaratustra foi construído segundo o padrão da câmara secreta do coração, que é o local onde a chama trina arde no altar do ser. O nosso sumo-sacerdote, que é o nosso Santo Cristo Pessoal, retira-se para esse local, para preservar a chama. Ele e outros mestres ascensos podem fazer-nos uma visita a esse local para instruirem a nossa alma. Zaratustra disse que seremos bem acolhidos no seu retiro quando o nosso coração estiver suficientemente desenvolvido. Ele não revelou a localização do seu retiro.

Fontes

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Masters and Their Retreats, s.v. “Zaratustra.”

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, “The Light of Persia—Mystical Experiences with Zarathustra,” Pérolas de Sabedoria, vol. 35, n° 35, 30 de agosto de 1992.

- ↑ Mary Boyce, "Zoroastrianos, Suas Crenças e Práticas Religiosas" (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1979), p. 1.

- ↑ R. C. Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” in The Concise Encyclopaedia of Living Faiths, ed. R. C. Zaehner (1959; reprint, Boston: Beacon Press, 1967), pp. 222, 209.

- ↑ Boyce, Zoroastrians, p. 18.

- ↑ Boyce, Zoroastrians, p. 19.

- ↑ Gathas: Yasnas 50.6, 46.2, 43.8, quoted in Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” p. 210.

- ↑ Boyce, Zoroastrians, p. 19.

- ↑ Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” p. 210.

- ↑ David G. Bradley, A Guide to the World’s Religions (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1963), p. 40.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Telephone interview with H. Michael Simmons, Center for Zoroastrian Research, 28 June 1992.

- ↑ Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” p. 210.

- ↑ R. C. Zaehner, The Dawn and Twilight of Zoroastrianism (Londres: Weidenfeld e Nicolson, 1961), p. 35.

- ↑ Dinkart 7.4.75-76, citado em Bernard H. Springett, Zoroaster, the Great Teacher (Londres: William Rider and Son, 1923), p. 25.

- ↑ Zaratustra, A Moment in Cosmic History – The Empowerment of Bearers of the Sacred Fire (Um Momento na História Cósmica – A Concessão de oider aos Portadores do Fogo Sagrado), Pérolas de Sabedoria, vol. 24, n° 13, 28 de março de 1981.

- ↑ Mary Boyce, ed. and trans., Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism (1984; reprint, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), p. 12.

- ↑ Boyce, Zoroastrians, p. 22.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 21.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 22; Boyce, Textual Sources, p. 13.

- ↑ Boyce, Zoroastrians, p. 22.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Boyce, Textual Sources, p. 14.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Gatha: Yasna 30, quoted in Zaehner, Dawn, p. 42.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Zaehner, Dawn, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Gatha: Yasna 45.2, quoted in Zaehner, Dawn, p. 43.

- ↑ Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” pp. 211, 210.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 211.

- ↑ Gatha: Yasna 48.10, quoted in Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” p. 211.

- ↑ Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” p. 211.

- ↑ Gatha: Yasna 32.11, quoted in Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” p. 211.

- ↑ Zaehner, Dawn, p. 36.

- ↑ John B. Noss, Man’s Religions, 5th ed. (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1974), p. 443.

- ↑ Ahuna Vairya, in Boyce, Textual Sources, p. 56.

- ↑ Simmons, telephone interview, 28 June 1992.

- ↑ Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” p. 213.

- ↑ Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” p. 221.

- ↑ Boyce, Zoroastrians, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Zaehner, Dawn, pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Springett, Zoroaster, p. 60.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 32.

- ↑ Boyce, Zoroastrians, p. 79.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 226.

- ↑ Zaehner, “Zoroastrianism,” p. 222.

- ↑ Farhang Mehr, The Zoroastrian Tradition: An Introduction to the Ancient Wisdom of Zarathustra (Rockport, Mass.: Element, 1991), p. 93.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 94, 93, 70; telephone interview with Farhang Mehr, 1 July 1992.

- ↑ Mehr, Zoroastrian Tradition, pp. 94–96.