Orphic Mysteries

The Orphic Mysteries were a set of religious beliefs and practices originating in ancient Greece which spread through the Mediterranean at the time of the Roman Empire. Their origin can be traced to the hero Orpheus, a legendary musician, prophet and poet in Greek myth.

The earliest Orphic literature dates from the sixth century B.C., surviving only in papyrus fragments, and Orphic poetry was recited in mystery rites and rituals of purification. The path of Orphism included an ascetic way of life and secret initatory rites, which aimed to free the soul from the round of rebirth and open the way to communion with the gods.

Both Plato and Pythagoras were students of Orphism.

Orpheus

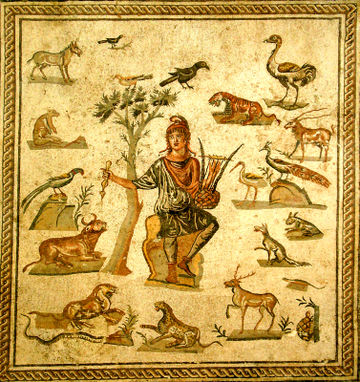

The legends regarding Orpheus are centered in his ability to charm all living things with his music and his descent into the underworld to reclaim his wife, Eurydice, from the grips of death. He also features in the legends of Jason and the Argonauts in their search for the Golden Fleece.

Orpheus’ father was said to be either Oeagrus, a Thracian king, or the god Apollo himself. According to some sources, his mother was the Muse Calliope, patroness of epic poetry. Apollo, the god of music, gave him his first lyre and taught him how to play it; his mother taught him to compose verses for his music

Historical origins

While scholars today consider Orpheus to be a creation of myth, most ancient authorities assumed he was a historical figure. This view is shared by Theosophical writers Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, who as a result of their clairvoyant probings of history, claimed that Orpheus lived around 7,000 B.C., about 1,000 years after the first city was built on the site that is now Athens. Besant and Leadbeater saw him as one of the great teachers of mankind. They write:

Orpheus [was] the Founder of the most ancient Orphic Mysteries, from which the later Mysteries of Greece were derived. About 7,000 B.C., He came, living chiefly in the forests, where He gathered his disciples around Him. There was no King to bid him welcome, so gorgeous Court to acclaim Him. He came as a Singer, wandering through the land, loving the life of Nature, her sunlit spaces and her shadowed forest retreats, averse to cities and the crowded haunts of men....

He taught by song, by music, music of voice and instrument, carrying a five-stringed musical instrument.... To this he sang, and wondrous was His music, the Devas drawing nigh to listen to the subtle tones; by sound He worked upon the astral and mental bodies of His disciples, purifying and expanding them; by sound he drew the subtle bodies away from the physical, and set them free in the higher worlds.... He showed his disciples living pictures, created by music, and in the Greek Mysteries this was wrought in the same way, the tradition coming down from Him. And He taught that Sound was in all things, and that if man would harmonize himself, then would the Divine Harmony manifest through him, and make all Nature glad. Thus he went through Hellas singing, and choosing here and there one who would follow Him, and singing also for the people in other ways, weaving over Greece a network of music, which should make her children beautiful and feed the artistic genius of her land....

From Hellas some of the disciples went to Egypt, and fraternised with the teachers of the Inner Light, and some went teaching as far afield as Java. And so the Sound went forth, even to the ends of the world.[1]

Beliefs

Orphism was the first Western system to combine the ideas of reincarnation and union with God. As far back as the seventh century B.C., the Orphics, like the Hindus, taught that within each of us resides a divine particle. They believed that this divine nature is buried in the body as in a tomb. They sought to release it through mystic initiations, secret rites and righteous living—during more than one lifetime if necessary.

Poems inscribed on thin, goldleaf tablets buried in the hands of Orphic believers in the fourth century B.C. clearly spell out the Orphic belief in divinization. These tablets, which were discovered in southern Italy, were designed to coach the dead on how to behave on the other side.

They instruct the initiate that after death he should recite the following words before the goddess Persephone: “I also avow me that I am of your blessed race.... I have paid the penalty for deeds unrighteous.... I have flown out of the sorrowful weary Wheel. I have passed with eager feet to the Circle desired.” The hoped-for response from Persephone is: “Happy and Blessed One, thou shalt be God instead of mortal.”[2]

When the verse speaks of flying out of the “sorrowful weary Wheel,” it is almost certainly referring to escaping the round of rebirth. And reaching the “Circle desired” indicates that the soul has arrived at the sphere outside the matter universe. What is this sphere?

The concept of heavenly spheres, found in the mystery religions, holds that the world is ruled by the seven planets: Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Each planet rules its own sphere. The Greeks believed that in order to attain divine union, the soul must pass through the seven concentric heavenly spheres, each one ruled by one of the planets, until it reaches the outermost sphere and escapes the matter universe altogether.

This journey is accomplished by giving up the negative energies or tendencies ruled by the planet. When the soul has purified herself fully, she is released from the wheel of rebirth. The “Circle desired” would therefore be the outermost sphere, the realm outside the dominion of the planets.

But the “Circle desired” could have a further meaning. The Greek word translated as circle literally means “crown.” Some mystery religions used attaining the crown to represent identification with, or becoming, God. Therefore, as one gives up the tendencies binding him to the matter universe, he is preparing himself to attain the crown, or union with God.

Legacy

As in the mystery religions of Dionysus, Osiris and Eleusis, central to the theology of the Orphic rites was the concept of resurrection. In each of these traditions, the divine or semi-divine hero was killed and raised from the dead, and the mysteries presented a path whereby initiates could aspire to their own resurrection and eternal life.

We see the same essential theme outplayed in the life of Jesus, who demonstrated physically what the mysteries had portrayed in myth and symbol and what their followers had glimpsed in their initiation ceremonies—and which some may even have experienced. Therefore, when Paul and the Apostles traveled throughout the Hellenistic world preaching Christ’s death and resurrection, they found a fertile field of people familiar with these concepts, who could see in this new dispensation the fulfillment of their spiritual path.

W. K. C. Guthrie, an authority on the Orphics, points out other parallels between the Orphic Mysteries and the message of Christianity:

The [Orphic] precepts are directed towards eradicating the sin (the Orphic would not have called it sin but impurity), and striving towards perfect union with the god who is in us all the time but stifled by the elements of impurity. They include therefore rites (teletai) both of purification and communion, of which the latter almost certainly involved being present at a recital and representation of the sufferings of Dionysos, our divine ancestor and our saviour....

If Orpheus ever approaches near to Christ, it is in this conception of communion on earth as not only a preparation for, but also a foretaste of the eternal life which is to be at one with God.[3]

For more information

Of the many original Orphic texts, few have survived from antiquity. Eighty-seven Orphic hymns or religious poems along with a commentary by the translator have been published in Thomas Taylor, The Hymns of Orpheus (1792).

For more information on Orphic beliefs, see: G. R. S. Mead, Orpheus (London: Theosophical Publishing Company, 1896); and W. C. K. Guthrie, Orpheus and Greek Religion (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993).

See also

Sources

Compiled and written by the editors.

The section “Beliefs” is taken from Elizabeth Clare Prophet with Erin L. Prophet, Reincarnation: The Missing Link in Christianity, pp. 71–73.

- ↑ Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater, Man: Whence, How and Whither (Adyar, India: Theosophical Publishing House, 1913) pp. 328–30.

- ↑ Compagno tablets (a) and (b), in Jane Harrison, Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion, 3d ed. (1922; reprint, New York: Meridian Books, 1955), p. 585.

- ↑ W. K. C. Guthrie, Orpheus and Greek Religion (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1952, 1993), pp. 206, 207.