Bodhidharma

[6th century A.D.] An Indian Buddhist missionary to China who founded the Ch’an, or Zen, sect of Buddhism in an effort to return the religion to the true spirit of Gautama’s teachings.

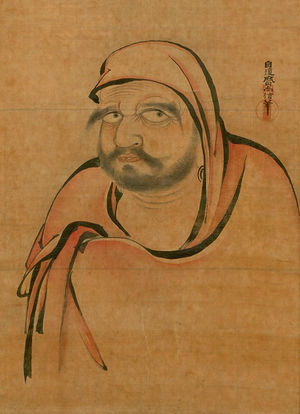

Bodhidharma taught that the Buddha was not to be found in books or images but in the heart of man and that the way to achieve enlightenment was through meditation. He spent nine years in intense meditation in a cave in northern China and was described as having a fierce disposition, penetrating eyes, and an abrupt and direct manner. According to Buddhist lore, in a fit of anger at having fallen asleep during meditation Bodhidharma cut off his eyelids. His intensity of purpose was characteristic of Ch’an devotees, who would undergo any austerity in order to attain the highest enlightenment.

Early life

In his introduction to The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma, Red Pine writes:

Bodhidharma was born around the year 440 in Kanchi, the capital of the Southern Indian kingdom of Pallava. He was a Brahman [a member of the priestly class] by birth and the third son of King Simhavarman. When he was young, he was converted to Buddhism, and later he received instruction in the Dharma from one called Prajnatara whom his father had invited to Magadha from the ancient Buddhist heartland. It was Prajnatara who also told Bodhidharma to go to China.[1]

One of the historians who chronicled Bodhidharma’s life tells us this:

He was a man of wonderful intelligence, bright and far-reaching; he thoroughly understood everything that he had ever learned. As his ambition was to master the doctrine of the Mahayana, he abandoned the white dress of a layman and put on the robe of monkhood, wishing to cultivate the seeds of holiness. He practiced contemplation and tranquilization. He knew well what was the true significance of worldly affairs. His virtues were more than a model to the world. He was very much grieved over the decline of orthodox teaching of the Buddha in the remoter parts of the earth. He finally made up his mind to cross over land and sea and come to China and preach his doctrine in the kingdom of Wei. Those that were spiritually inclined gathered about him full of devotion, while those that could not rise above their own one-sided views talked about him slanderingly.[2]

Bodhidharma and the Emperor of China

Dr. Thich Thien-An in his book Zen Philosophy, Zen Practice, says:

At the time of his arrival, the ruler of China was Emperor Wu-Ti of the Liang dynasty. Emperor Wu-Ti was an ardent Buddhist, a scholar as well as a supporter and devotee. Through his contacts with other Buddhist masters, he had come to understand Buddhist philosophy very well. When he heard that the great master Bodhidharma had arrived in China, he was beside himself with delight and promptly invited the master to his court....

When Bodhidharma entered the court, the Emperor, after paying his proper respects, spoke to the Master thus: “For a long time I have used my own money to support many Buddhist temples and ordain many Buddhist monks and nuns. I have built schools for children and hospitals for the sick and ages, and aged. I have printed many Buddhist texts for free distribution to the people. I have done so many good things for Buddhism and for my people. Would you please tell me how much merit I will get?” Without a moment’s hesitation Bodhidharma answered: “No merit at all.”

The response struck the Emperor like a slap. The other masters had all taught him quite differently. “Do good,” they said, “and you will receive good; do bad and you will receive bad. Effects follow causes as shadows follow figures.”...

The Emperor then asked Bodhidharma another question: “Would you please tell me, what is the essence of Buddhism?” Short and sharp the answer came, “No essence at all.”

The Emperor was stunned. No essence at all? When he had asked the other masters this question, they explained, with many words, arguments, illustrations and proofs, the basic doctrines of Buddhism....

Why did Bodhidharma answer the way he did? Perhaps he wanted to say that all the teachings in Buddhism are but methods to be practiced, skillful means or expedients, and that what constitutes the essence for one man may not be the essence for another.... Or perhaps he wanted to say that the original Mind of Enlightenment is the All-illumining Void in which there is nothing to be grasped and no one to grasp, and therefore no essence at all. But Bodhidharma was not the kind of man to waste words. Therefore, short and sharp the answer came, “No essence at all.”

This answer did not please the Emperor. However, he tried to be patient and asked one more question of Bodhidharma: “You say that, according to Buddhism, everything is nothing, that all things have no essence. Well then, who is he that is talking with me now?” [Bodhidharma answered] “I do not know.” This reply shocked the Emperor. He lost his patience, dismissed Bodhidharma from his court and retired to his chambers, his head swirling in confusion.

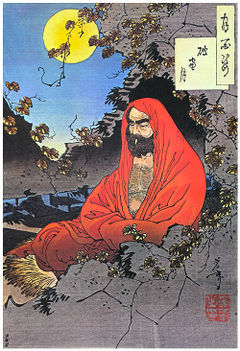

Meanwhile, left to himself, Bodhidharma thought: “This man is a Buddhist scholar, and yet even he could not understand. Perhaps conditions are not yet favorable enough for me to teach.” So he went to the Shao-Lin monastery in the state of Wei, sat cross-legged before a wall and entered into a deep state of meditation. He sat like this for nine years, waiting for conditions to ripen, waiting for someone to appear who would be capable of receiving the transmission of the wonderful Buddha Mind, that priceless treasure he had traveled all the way from India to China to transmit.[3]

The Shaolin temple later became famous for training monks in kung fu, and Bodhidharma is honored as the founder of this martial art.

Meditation

Bodhidharma’s years of concentrated meditation earned him the title “wall-gazing brahman.” Some Zen Buddhists do not take Bodhidharma’s “wall-gazing” literally. Instead, they say it is symbolic of the state of desirelessness and the “strong mind” that is necessary to achieve enlightenment.

Buddhist scholar D. T. Suzuki believes that the deeper meaning of Bodhidharma’s wall-gazing may be related to the Buddhist teaching that only “‘the strong mind’ is characteristic of one who can enter upon the realm of reality. So long as there are ‘pantings’ (or gaspings) in the mind, it is not free, it is not liberated.... The mind must be ‘strong’ or firm and steady, self-possessed and concentrating,”[4] simply not moved from its resolution. Bodhidharma taught this concept to his chief disciple when he told him, “Externally keep yourself away from all relationships, and, internally, have no pantings [that is, hankerings] in your heart.”[5]

If you hanker after this and you hanker after that and hanker after the next thing, how long will it take you to sustain the mind of Buddha where you are? Each interruption, each disruption of the joy of internalizing the Buddha weakens your resolve, weakens your momentum. It’s like starting and stopping a train or a car. Start and stop and start and stop, and pretty soon you live your life in a frantic sense of starting and stopping instead of controlling the mind, therefore controlling one’s environment by the mind. This is the point of Zen. Bodhidharma said to his chief disciple, “When your mind is like unto a straight-standing wall you may enter into the Path.”[6]

Artists often portray Bodhidharma’s fierce concentration by depicting him with bulging eyes and a gruff, intense demeanor. Alan Watts explains in his book The Way of Zen:

A legend says that Bodhidharma once fell asleep in meditation and was so furious that he cut off his eyelids, and falling to the ground they arose as the first tea plant. Tea has thereafter supplied Zen monks with a protection against sleep.... Another legend holds that Bodhidharma sat so long in meditation that his legs fell off. Hence the delightful symbolism of those Japanese Daruma dolls which represent Bodhidharma as a legless roly-poly so weighted inside that he always stands up again when pushed over. A popular Japanese poem says of the Daruma doll, ..“Such is life— / Seven times down / Eight times up!”[7]

Bodhidharma and Hui-k’o

During Bodhidharma’s stay near the Shaolin monastery, he met the man who was to become his chief disciple. He was a scholar named Hui-k’o. Hui-k’o begged Bodhidharma to teach him, but the master just ignored him. Scholar Heinrich Dumoulin paints the scene:

Determined to attain the Tao, the highest enlightenment, at any cost, Hui-k’o besieged Bodhidharma day and night with his entreaties. Bodhidharma, however, paid no attention to him. On the 9th of December—the chronicle marks it well—the decisive moment arrived. It was an icy cold winter night. A storm was raging and the wind was whipping the snow about wildly. Moved to compassion, the master looked upon the figure standing there motionless before him in the cold and asked him what he wanted. In so doing, he let him know that one final, decisive effort was needed. Hui-k’o drew out a sharp knife and cut off his left arm at the elbow, presenting it to Bodhidharma. At that the master accepted him as a disciple.[8]

The Zen master Sokei-An says that “many students of the Zen school do not accept this cutting off of the arm in the literal sense. ‘To cut off’ is interpreted as casting aside all traditional methods for arriving at the final truth.”[9]

Dr. Thich Thien-An describes the next part of the legend: “Seeing the sincerity of the monk, he [Bodhidharma] realized that here was a man capable of receiving the Dharma.”

When Bodhidharma asked him, “‘What do you want from me?’ Kuang [Hui-k’o] replied: ‘For a long time I have tried to keep my mind calm and pure by practicing meditation. But when I meditate, I become bothered by many thoughts and cannot keep my mind calm. Would you please tell me how to pacify my mind?’

Bodhidharma smiled and answered: “‘Bring me that mind, and I will help you pacify it.’ Kuang stopped, searched within looking for his mind, and after a time said: ‘I am looking for my mind, but I can’t find it.’ ‘There,’ Bodhidharma declared, ‘I have already pacified it!’ With these words, Kuang’s mad mind suddenly halted. A veil lifted. He was enlightened.”[10]

The more we surrender, the more we realize that nothing of this world really means anything to us; that what we are really seeking is enlightenment, such as this disciple who followed Bodhidharma until finally he was accepted. Bodhidharma was convinced that he had the determination to see through this path, because he gave so much, which was all of his life, for the gift of enlightenment. In the very first lesson that is recounted, he receives a lifting of the veil of that human consciousness and enters into the enlightenment through the crown chakra.

Thich Thien-An continues:

When he took the mind to be real, then the wandering mind disturbed him in his meditation. But now that he could not find that wandering mind, he realized the mind is no-mind, that nothing can be disturbed. And from that no-mind he realized the One-Mind.[11]

No-mind

If you think your mind is real, then you are giving it the power to disturb you no matter what it is doing. But if Hui-k’o could not find the wandering mind, he realized that his mind was no-mind, and therefore that something that is nothing cannot be disturbed. The no-mind is the mind emptied, the mind that is not a mind at all. When we get rid of that mind, this vessel is a vessel exclusively for the Divine Mind.

We may perceive the Divine Mind through the central nervous system, through every cell of our body, through every organ. We can say that the Divine Mind is in every cell, in every electron. So we are a chalice for the One-Mind. But if we are determined to go through the human mind or to depend upon the brain, then we will not have the emptiness to receive the One-Mind.

To have the realization that enlightenment—or the piercing of a koan—did not come through your brain but came through the higher consciousness of your Divine Mind directly without having to pass through the brain is a wonderful experience. It proves the path of Zen. It proves eternal life. It proves that even people who are brain-dead are alive and well and one with the Universal Mind of God. It proves that we exist apart from this body.

And when we enter the Dharmakaya, and then the Sambhogakaya, representing the Christ, and the Nirmanakaya, the lower self, we are weaning ourselves from dependency upon the flesh. And it is that dependency which makes us fear death, fear the afterlife, fear our beginnings and our endings and the days in between. The joy of Zen is to daily internalize eternal life, the infinite nature of being, and the Buddha Mind.

The passing of Bodhidharma

Although Bodhidharma is spiritual father to millions of Zen Buddhists today, he evidently had few followers in his own lifetime. The chronicles of his life mention only three disciples. According to one account, Bodhidharma died after he was poisoned by a jealous monk.[12] Another account says he died of old age sometime after his rivals had tried to poison him five times. Hui-k’o became the second patriarch of Chinese Zen Buddhism.

Red Pine says:

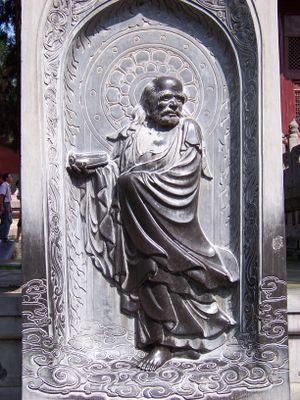

According to Tao-yuan, Bodhidharma’s remains were interred near Loyang at Tinglin Temple on Bear Ear Mountain. Tao-yuan adds that three years later an official met Bodhidharma walking in the mountains of Central Asia. He was carrying a staff from which hung a single sandal, and he told the official he was going back to India. Reports of this meeting aroused the curiosity of other monks, who finally agreed to open Bodhidharma’s tomb. But inside all they found was a single sandal, and ever since then Bodhidharma has been pictured carrying a staff from which hangs the missing sandal.[13]

The essence of Zen

► Main article: Zen

Tradition says that Bodhidharma brought a special message from India to China, which encapsulates Zen philosophy. It reads, “A special transmission outside the scriptures; no dependence upon words and letters.” These are the statements which encapsulate Zen philosophy: 1) “A special transmission outside the scriptures,” 2) “No dependence upon words and letters,” 3) “Direct pointing at the mind of man,” and 4) “Seeing into one’s nature and the attainment of Buddhahood.”[14]

Bodhidharma’s message is that we cannot realize ultimate truth or attain our own Buddhahood by means of words and letters. We must discover for ourselves our real nature, which is the Buddha-nature.[15]

How shall you define the Buddha-nature within you? You will think upon those virtues and attributes that you would imagine Bodhidharma, Gautama Buddha, Amitabha, the Five Dhyani Buddhas and many, many other Buddhas unnamed would have in their little bags; what they would have as virtue: strength of mind, oneness of purpose, profound compassion, grace, mercy, nonattachment to the fruit of action, doing things for the sake of doing good things rather than for reward or recognition.

Think of all those qualities you would imagine the Buddha to have and realize that those qualities are the Buddha-nature. They are seeds, and as you water them and let the sun shine upon them, they come up through the earth, they defy gravity, they keep growing and they show us those things that have germinated from within our Buddha-nature.

This is a reason for living. This is a reason for being. We can have many achievements in this life, but the realization of the Buddha-nature gives us spherical being and the ability to reach out and do those things that the Buddhas have done whereby they attained full outer manifestation of Buddhahood.

Final embodiment

In a dictation given October 8, 1994, El Morya revealed that Bodhidharma was one of the incarnations of Lanello. He said:

Lanello comes to you often with the terse comment or merely a look of his eyes.... I announce this so that you will understand what sort of Masters we are—Zen, terse, concise, humble, truly not making much of the ego of the self but embracing the cosmos and the great T’ai Chi.[16]

See also

Sources

Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 31, no. 77.

Elizabeth Clare Prophet, August 21, 1994.

- ↑ Red Pine, The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma (San Fransisco: North Point Press, 1989), pp. ix–x.

- ↑ D. T. Suzuki, Essays in Zen Buddhism, First Series (New York: Grove Press, 1961), pp. 179–80.

- ↑ Thich Thien-An, Zen Philosophy, Zen Practice (Emeryville, Calif.: Dharma Publishing, 1975) pp. 17–20.

- ↑ Suzuki, Essays in Zen Buddhism, p. 185, n. 2.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 185.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Alan Watts, The Way of Zen (New York: Vintage Books, 1957), pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Heinrich Dumoulin, Zen Buddhism: A History, Vol. 1, India and China (Bloomington, Indiana: World Wisdom, 1988, 2005), p. 92.

- ↑ Nancy Wilson Ross, ed., The World of Zen: An East-West Anthology (New York: Random House, 1960), p. 60.

- ↑ Thich Thien-An, Zen Philosophy, Zen Practice, p. 21.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Red Pine, The Zen Teachings of Bodhidharma, p. xiv.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Thich Thien-An, Zen Philosophy, Zen Practice, p. 17.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 25.

- ↑ Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 37, no. 40, October 2, 1994.