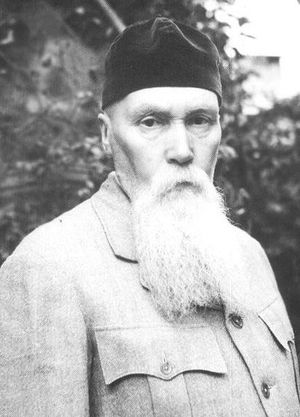

Nicolás Roerich

Nicolás Roerich fue un artista, arqueólogo, escritor, erudito, conferencista, diseñador de vestuarios y escenario, poeta, místico y explorador mundialmente conocido. Él y su esposa, Helena Roerich, prestaron servicio a principios del siglo XX como amanuenses de los maestros ascendidos El Morya y Maitreya. Nicolás ascendió al final de esa vida.

Early life

Nació en San Petersburgo el 9 de octubre de 1874, como primer hijo de Konstantin y María Roerich. El nombre Nicolás significa «el que vence», y Roerich significa «rico en gloria». Su padre era un prominente abogado y notario y Nicolás pasaba mucho tiempo cuando era joven en la gran propiedad campestre de la familia, Isvara, localizada a unas cincuenta millas al sureste de San Petersburgo. Allí, en la belleza del norte de Rusia, se encendió un amor por la naturaleza en el joven Nicolás que duraría toda su vida. En Isvara desarrolló una pasión por la caza y un ávido interés por la historia natural, la arqueología y la historia de Rusia. Le gustaba la música y montar a caballo.

Su padre quería que estudiara leyes, pero Nicolás quería entregarse al arte. Nicolás resolvió la situación inscribiéndose simultáneamente en la facultad de leyes de la Universidad Imperial y en la Academia Imperial de las Artes.

En 1898 Nicolás llegó a ser asistente del director del museo de la Sociedad para el Fomento de las Artes. En septiembre de 1900 fue a París a estudiar arte. En el verano de 1901 Nicolás regresó a San Petersburgo y en octubre se casó con Helena Ivanovna Shaposhnikova. Helena era una pianista consumada y llegó a ser considerada como una distinguida dama de letras y una escritora prolífica de la tradición esotérica oriental. Ella era su llama gemela, una inspiración y un apoyo para Nicolás en toda su vida. Nicolás y Helena tuvieron dos hijos, Yuri y Svetoslav.

A principios de 1900 los Roerich viajaron extensamente por Rusia y Europa. Durante estos viajes, el profesor Roerich pintó, emprendió excavaciones arqueológicas, estudió arquitectura, dio conferencias y escribió sobre arte y arqueología. En 1906 fue promovido de secretario a director de la escuela de la Sociedad para el Fomento de las Artes.

En 1907 comenzó a aplicar sus talentos al escenario y al diseño de vestuarios. Esto se convirtió en una profesión satisfactoria y llena de éxito para Roerich. Diseñó escenarios y vestuarios para el ballet de Diaghilev y producciones de ópera, como La consagración de la primavera, de Stravinsky, y para casi todas las óperas de Wagner y muchas de Rimsky-Korsakov.

La familia Roerich se marchó de Rusia hacia Finlandia en 1918, poco antes de que la frontera entre Finlandia y la Unión Soviética se cerrara permanentemente. A invitación del director del Instituto de Arte de Chicago, Roerich fue a los Estados Unidos en 1920. Viajó mucho, dio conferencias y exhibió sus obras. Durante su estancia en ese país, Roerich fundó el Instituto Maestro de las Artes Unidas, una sociedad internacional de artistas llamada Cor Ardens («Corazón Ardiente»), y un centro de arte internacional en Nueva York llamado Corona Mundi («Corona del Mundo»). Como tributo a Roerich, se estableció el Museo Roerich en Nueva York en 1923.

Obra de arte

Muchas de las obras de Roerich son escenas magníficas de la naturaleza, y sus temas están inspirados en la historia, la arquitectura y la religión. Sus pinturas son místicas, alegóricas e incluso proféticas. Entre 1912 y 1914 sus pinturas reflejaron con frecuencia un sentido de cataclismo inminente. Una de ellas, El último ángel (1912), representa una intensa conflagración que envuelve una ciudad; por encima de la ciudad, rodeado de ondeantes nubes de humo, un ángel con espada y escudo anuncia el Juicio Final. En 1936, justo antes de la Segunda Guerra Mundial, Roerich pintó Armagedón. Los tejados de una ciudad son visibles entre las nubes de humo, con las siluetas de soldados marchando en un primer plano por la parte baja del cuadro.

El estilo artístico de Roerich es difícil de describir porque, como lo expresó Claude Bragdon, pertenece a una fraternidad elegida de artistas –como da Vinci, Rembrandt, Blake y, en música, Beethoven– cuyas obras poseen «una cualidad única, profunda y realmente mística que las diferencia de sus contemporáneos, haciendo imposible clasificarlas en ninguna categoría conocida ni relacionarlas con escuela alguna, porque sólo se parecen a sí mismas; y se parecen entre sí, como una orden de iniciados ajena al espacio y al tiempo»Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; refs with no name must have content.

Journey to the East

Nicolás Roerich recibió una gran influencia de la cultura oriental. Había deseado por mucho tiempo viajar a Oriente con el fin de estudiar la antigua cultura personalmente; y en 1923 zarpó hacia la India. Residió por un tiempo en Sikkim (entonces un reino colindante al noreste de la India) mientras hacía los últimos planes de una expedición a Asia Central. Roerich escribió sobre su fascinación con las montañas:

Todos los instructores viajaron a las montañas. El conocimiento más elevado, los cantos más inspirados, los más soberbios sonidos y colores son creados en las montañas. En las montañas más altas está lo Supremo. Las altas montañas son los testigos de la gran realidadCite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; refs with no name must have content.

¡Himalayas! Aquí está la Morada de los Rishis. Aquí resonó la sagrada Flauta de Krishna. Aquí tronó el Bendito Buda Gautama. Aquí se originaron todos los Vedas. Aquí vivió Pandavas. Aquí, Gesar Khan. Aquí, Aryavarta. Aquí está Shambala. Himalayas, Joya de la India. Himalayas, Tesoro del mundo. Himalayas, el sagrado Símbolo del AscensoCite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; refs with no name must have content.

Tanto Nicolás como Helena Roerich tenían un gran interés por la filosofía y la religión orientales. Muchas de sus pinturas contienen deidades tanto orientales como occidentales, santos y sabios. Su serie «Estandartes de Oriente» refleja no sólo líderes espirituales del pasado sino las esperanzas de Oriente hacia un líder que ha de llegar. Roerich captó esas esperanzas en sus pinturas de Maitreya y la Madre del Mundo.

En 1925 Roerich comenzó su expedición a Asia Central con Helena, su hijo Yuri y varios acompañantes Europeos. Roerich escribió sus metas:

Por supuesto, como artista mi aspiración principal en Asia es hacia un trabajo artístico… Además de sus metas artísticas, nuestra expedición planeaba estudiar la posición de los antiguos monumentos de Asia Central, observar el actual estado de las religiones y los credos y anotar los rastros de las grandes migraciones de las nacionesCite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; refs with no name must have content.

Roerich’s party traveled 15,500 miles through Central Asia in an arduous and often dangerous trek that took more than four years. Despite overwhelming obstacles, Roerich executed hundreds of paintings during the journey.

While on this expedition, Roerich discovered legends and manuscripts recounting the journey Jesus took to the East during his so-called lost years between the ages of twelve and thirty. The same or similar manuscripts were also found by Russian journalist Nicolas Notovitch and Swami Abhedananda at Himis monastery in Ladakh.[1]

At the conclusion of the Central Asian expedition in 1928, the Roerichs permanently settled in the Kulu Valley in India. There they founded the Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute to study archaeology, linguistics and botany.

The Banner of Peace

One of the goals of Roerich’s lifelong pursuit of preserving the world’s cultural heritage came to fruition in 1935 with the signing of the Roerich Pact treaty at the White House by representatives of the countries comprising the Pan-American Union. Under the pact, nations at war were obliged to respect museums, universities, cathedrals and libraries as they did hospitals. Just as hospitals flew the Red Cross flag, cultural institutions would fly Roerich’s “Banner of Peace,” a flag that has a white field with three red spheres in the center surrounded by a red circle. Roerich believed that by protecting culture, the spiritual health of the nations would be preserved.

Roerich was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1929 and 1935 for his efforts to promote international peace through art and culture and to protect art treasures in time of war. World War II interrupted his activities and those of the Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute, and Roerich devoted himself to helping victims of the war. He also donated money from the sale of his paintings and books to the Soviet Red Cross.

In the summer of 1947, Roerich had heart surgery but was soon back at his easel. One of the last works Roerich painted is called The Master’s Command. It depicts a white eagle flying toward a devotee who is meditating in the lotus posture atop a high cliff overlooking a mountain valley. On December 13, 1947, while Roerich was working on a variant of this picture, his heart suddenly failed and his soul took flight to higher octaves. He was seventy-three years old.

Legacy

Throughout his life, Nicholas Roerich found the time to be involved in a multitude of activities and to do them all well. His spiritual life was the wellspring from which his literary and artistic vision arose. In an article about the character and work of his father, Svetoslav Roerich summed up the artist’s quest for inner spirituality:

He was a great patriot and he loved his Motherland, yet he belonged to the entire world and the whole world was his field of activity. Every race of men was to him a brotherly race, every country a place of special interest and of special significance. Every religion was a path to the Ultimate and to him life meant the great gates leading into the Future.... Every effort of his was directed towards the realisation of the Beautiful and his thoughts found a masterful embodiment in his paintings, writings and public life....

Through all his paintings and writings runs the continuous thread of a great message—the message of the Teacher calling to the disciples to awaken and strive towards a new life, a better life, a life of beauty and fulfillment.[2]

His service as an ascended master

The ascended master Nicholas Roerich says:

I am grateful to address you today, to speak to you from the plane of the ascended masters that you might know that one from among you has graduated to this level and that you might accomplish the same. Never tire, then, in the work that is your dharma, your duty to be the wholeness of yourself. Never be frustrated that you are misunderstood or before your time in your understanding of the stars, the universes, the mountains and the petals of a flower. I have indeed fought the good fight, and I have won.[3]

He asks us to call to him, and he stresses the use of the violet flame:

I ask you, chelas of the ascended masters, to include my name in your decrees and preambles, as I work closely with El Morya, K.H. and D.K., and Lanello. I work closely with them for the bringing together of all those who are on the path of the sacred fire.[4]

For more information

For more information about Nicholas Roerich and his magnificent artwork, see the website of the Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York, www.roerich.org.

Sources

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Masters and Their Retreats, s.v. “Nicholas Roerich.”

- ↑ Roerich, Notovotch and Abhedananda all published their translations of these texts describing Jesus’ journey to the East. All three accounts are included in Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Lost Years of Jesus: Documentary Evidence of Jesus’ 17-Year Journey to the East.

- ↑ Svetoslav Roerich, “My Father,” in Nicholas Roerich (New York: Nicholas Roerich Museum, 1974), p. 15.

- ↑ Nicholas Roerich, “Be the Unextinguishable Ones!” Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 33, no. 44, November 11, 1990.

- ↑ Ibid.