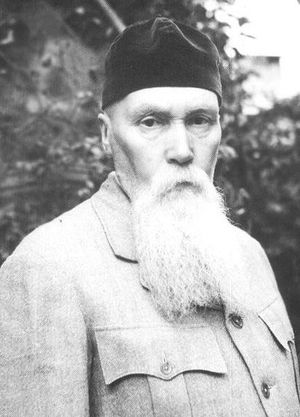

Nicholas Roerich

Nicholas Roerich foi um artista conhecido no mundo inteiro, um arqueólogo, escritor, erudito, palestrante, designer de roupas, cenógrafo, poeta, místico e explorador. No início do século vinte, ele e Helena Roerich, sua esposa, serviram como amanuenses dos Mestres Ascensos El Morya e Maitreya. Nicholas ascendeu no final dessa vida.

Início de vida

Filho primogênito de Konstantin e Maria Roerich, Nicholas nasceu em São Petersburgo, em 9 de outubro de 1874. O nome Nicholas significa “aquele que triunfa”, e Roerich significa “rico em glórias”. Seu pai era um advogado e tabelião proeminente. Nicholas passou a maior parte da juventude na imensa propriedade rural da família, em Isvara, cerca de trinta e cinco quilômetros a sudoeste de São Petersburgo. Ali, em meio às belezas do norte da Rússia, o jovem Nicholas desenvolveu um amor pela natureza que durou toda a sua vida. Em Isvara ele também desenvolveu a paixão pela caça e um grande interesse pela história natural, pela arqueologia e pela história da Rússia. Nicholas também apreciava a música e a equitação.

O pai queria que ele estudasse Direito, mas Nicholas interessava-se pelas artes, e resolveu a situação matriculando-se simultaneamente na faculdade de direito da Universidade Imperial e na Academia Imperial de Artes.

Em 1898, Nicholas ocupou o cargo de diretor-assistente do museu da Sociedade para o Encorajamento das Artes. Em setembro de 1900, foi para Paris estudar arte, voltando a São Petersburgo no verão de 1901. Em outubro, casou-se com Helena Ivanovna Shaposhnikova. Pianista talentosa, Helena também se tornou uma renomada mulher de letras e escritora profícua da tradição esotérica das religiões orientais. Helena era a chama gêmea de Nicholas e inspirou-o e apoiou-o durante toda a vida. O casal teve dois filhos, George e Svetoslav.

No início dos anos 1900, os Roerichs viajaram por toda a Rússia e pela Europa. Nessas viagens, o professor Roerich pintava, liderava escavações arqueológicas, estudava arquitetura, fazia palestras e escrevia sobre arte e arqueologia. Em 1906, foi promovido de secretário a diretor da escola da Sociedade para o Encorajamento das Artes.

Em 1907, Nicholas Roerich empregou o seu talento na cenografia e em figurinos de teatro; uma carreira bem-sucedida na qual se realizou. Ele desenhou cenários e figurinos para o balé de Diaghilev e para muitas óperas, incluindo a Sagração da Primavera, de Stravinsky, para quase todas as óperas de Wagner e muitas da autoria de Rimsky-Korsakov.

A família Roerich trocou a Rússia pela Finlândia, em 1918, pouco antes de a fronteira entre os dois países ser fechada permanentemente. Em 1920, a convite do diretor do Chicago Art Institute, (Instituto de Arte de Chicago) Roerich foi para os Estados Unidos por onde viajou extensivamente, palestrou e exibiu os seus trabalhos. Enquanto esteve ali, fundou o Instituto Mestre de Artes Unidas – uma sociedade internacional de artistas denominada Cor Ardens (que significa Coração Flamejante) – e um centro internacional de arte, em Nova York, batizado de Corona Mundi (que significa Coroa do Mundo). Em sua homenagem, em 1923, foi criado o Museu Roerich, na cidade de Nova York.

Obras de Arte

Muitas obras de Roerich retratam cenas magníficas da natureza e temas inspirados na história, na arquitetura e na religião. As suas pinturas são místicas, alegóricas e até mesmo proféticas. Os quadros que pintou entre 1912 e 1914 refletem geralmente um sentimento de cataclismo iminente. Um deles, O último Anjo (1912), representa um incêndio de enormes proporções envolvendo uma cidade. Sobre o local, cercado por nuvens de fumaça, há um anjo, carregando espada e escudo, que anuncia o Juízo Final. Em 1936, pouco antes da Segunda Guerra Mundial, Roerich pintou Armagedom. No quadro, vemos os telhados de uma cidade entre nuvens de fumaça e, em primeiro plano, na parte inferior da obra, a silhueta de soldados em marcha.

Não é fácil descrever o estilo artístico de Roerich porque, segundo Claude Bragdon, ele pertence a uma seleta fraternidade de artistas – que inclui da Vinci, Rembrandt, Blake e, na música, Beethoven – cujas obras apresentam “uma qualidade única, profunda e mística, que os diferencia dos seus contemporâneos, tornando impossível classificá-los em qualquer categoria conhecida, ou vinculá-los a qualquer escola, visto serem figuras únicas que se assemelham a si mesmas – e uns aos outros, como uma ordem de iniciados fora do tempo e do espaço”.[1]

Jornada ao Oriente

Nicholas Roerich foi altamente influenciado pela cultura oriental. Durante muito tempo, acalentou o desejo de viajar ao Oriente para estudar, in loco, a cultura antiga e, em 1923, foi para a Índia. Enquanto finalizava os planos para empreender uma expedição à Ásia Central, morou por um tempo em Sikkim, à época um reino fronteiriço no noroeste da Índia. Sobre o encantamento que as montanhas despertavam nele, Roerich escreveu:

“Todos os mestres viajaram para as montanhas. O conhecimento mais elevado, as canções mais inspiradas, as cores e os sons mais soberbos são criados nas montanhas. Nas montanhas mais altas encontra-se o Supremo. As montanhas altas permanecem como testemunhas da realidade maior.[2]

Himalaias! Aqui é a Morada dos Rishis. Aqui soou a Flauta Sagrada de Krishna. Aqui o abençoado Gautama Buda clamou. Aqui originaram-se todos os Vedas. Aqui viveram os Pandavas. Aqui – Gesar Khan. Aqui – Aryavarta. Aqui está Shambhala. Himalaias – Joia da Índia. Himalaias – Tesouro do Mundo. Himalaias – o Símbolo Sagrado da Elevação”.[3]

Nicholas e Helena Roerich tinham um interesse enorme pela filosofia e pela religião do Oriente. Muitas das pinturas de Nicholas retratam divindades, santos e sábios orientais e ocidentais. A série “Estandartes do Oriente” representa não apenas os líderes espirituais do passado, como também as esperanças do Oriente pela vinda de um futuro líder. Sempre que pintou Maitreya e a Mãe do Mundo, Roerich capturou essas esperanças.

In 1925 Roerich started on his Central Asian expedition with Helena, his son George and several other Europeans. Roerich wrote of his goals:

Of course, as an artist my main aspiration in Asia was towards artistic work.... In addition to its artistic aims, our Expedition planned to study the position of the ancient monuments of Central Asia, to observe the present condition of religions and creeds, and to note the traces of the great migrations of nations.[4]

Roerich’s party traveled 15,500 miles through Central Asia in an arduous and often dangerous trek that took more than four years. Despite overwhelming obstacles, Roerich executed hundreds of paintings during the journey.

While on this expedition, Roerich discovered legends and manuscripts recounting the journey Jesus took to the East during his so-called lost years between the ages of twelve and thirty. The same or similar manuscripts were also found by Russian journalist Nicolas Notovitch and Swami Abhedananda at Himis monastery in Ladakh.[5]

At the conclusion of the Central Asian expedition in 1928, the Roerichs permanently settled in the Kulu Valley in India. There they founded the Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute to study archaeology, linguistics and botany.

The Banner of Peace

One of the goals of Roerich’s lifelong pursuit of preserving the world’s cultural heritage came to fruition in 1935 with the signing of the Roerich Pact treaty at the White House by representatives of the countries comprising the Pan-American Union. Under the pact, nations at war were obliged to respect museums, universities, cathedrals and libraries as they did hospitals. Just as hospitals flew the Red Cross flag, cultural institutions would fly Roerich’s “Banner of Peace,” a flag that has a white field with three red spheres in the center surrounded by a red circle. Roerich believed that by protecting culture, the spiritual health of the nations would be preserved.

Roerich was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1929 and 1935 for his efforts to promote international peace through art and culture and to protect art treasures in time of war. World War II interrupted his activities and those of the Urusvati Himalayan Research Institute, and Roerich devoted himself to helping victims of the war. He also donated money from the sale of his paintings and books to the Soviet Red Cross.

In the summer of 1947, Roerich had heart surgery but was soon back at his easel. One of the last works Roerich painted is called The Master’s Command. It depicts a white eagle flying toward a devotee who is meditating in the lotus posture atop a high cliff overlooking a mountain valley. On December 13, 1947, while Roerich was working on a variant of this picture, his heart suddenly failed and his soul took flight to higher octaves. He was seventy-three years old.

Legacy

Throughout his life, Nicholas Roerich found the time to be involved in a multitude of activities and to do them all well. His spiritual life was the wellspring from which his literary and artistic vision arose. In an article about the character and work of his father, Svetoslav Roerich summed up the artist’s quest for inner spirituality:

He was a great patriot and he loved his Motherland, yet he belonged to the entire world and the whole world was his field of activity. Every race of men was to him a brotherly race, every country a place of special interest and of special significance. Every religion was a path to the Ultimate and to him life meant the great gates leading into the Future.... Every effort of his was directed towards the realisation of the Beautiful and his thoughts found a masterful embodiment in his paintings, writings and public life....

Through all his paintings and writings runs the continuous thread of a great message—the message of the Teacher calling to the disciples to awaken and strive towards a new life, a better life, a life of beauty and fulfillment.[6]

His service as an ascended master

The ascended master Nicholas Roerich says:

I am grateful to address you today, to speak to you from the plane of the ascended masters that you might know that one from among you has graduated to this level and that you might accomplish the same. Never tire, then, in the work that is your dharma, your duty to be the wholeness of yourself. Never be frustrated that you are misunderstood or before your time in your understanding of the stars, the universes, the mountains and the petals of a flower. I have indeed fought the good fight, and I have won.[7]

He asks us to call to him, and he stresses the use of the violet flame:

I ask you, chelas of the ascended masters, to include my name in your decrees and preambles, as I work closely with El Morya, K.H. and D.K., and Lanello. I work closely with them for the bringing together of all those who are on the path of the sacred fire.[8]

For more information

For more information about Nicholas Roerich and his magnificent artwork, see the website of the Nicholas Roerich Museum, New York, www.roerich.org.

Sources

Mark L. Prophet and Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Masters and Their Retreats, s.v. “Nicholas Roerich.”

- ↑ Claude Bragdon, Introductrion, em Altai Himalaya: A Travel Diary, de Nicholas roerich (Brookfield, Conn. : Arun Press, 1929), p. xix.

- ↑ Nicholas Roerich, Himalayas: Abode of Light (Bombay: Nalanda Publications, 1947) p. 21, Jaqueline Decter, Nicholas Roerich: the Life and Art of A Russian Master (Rochester, Vt: Park Street Press, 1989), p. 141.

- ↑ Nicholas Roerich, Himalayas, p. 13, Nicholas Roerich, de Decter, p. 203.

- ↑ Nicholas Roerich, Heart of Asia (New York: Roerich Museum Press, 1929), pp. 7, 8.

- ↑ Roerich, Notovotch and Abhedananda all published their translations of these texts describing Jesus’ journey to the East. All three accounts are included in Elizabeth Clare Prophet, The Lost Years of Jesus: Documentary Evidence of Jesus’ 17-Year Journey to the East.

- ↑ Svetoslav Roerich, “My Father,” in Nicholas Roerich (New York: Nicholas Roerich Museum, 1974), p. 15.

- ↑ Nicholas Roerich, “Be the Unextinguishable Ones!” Pearls of Wisdom, vol. 33, no. 44, November 11, 1990.

- ↑ Ibid.